The Arcades: Contemporary Art and Walter Benjamin

This exhibition of contemporary artworks presents photography, video, sculpture, and painting seen through the lens of influential philosopher Walter Benjamin’s magnum opus The Arcades Project.

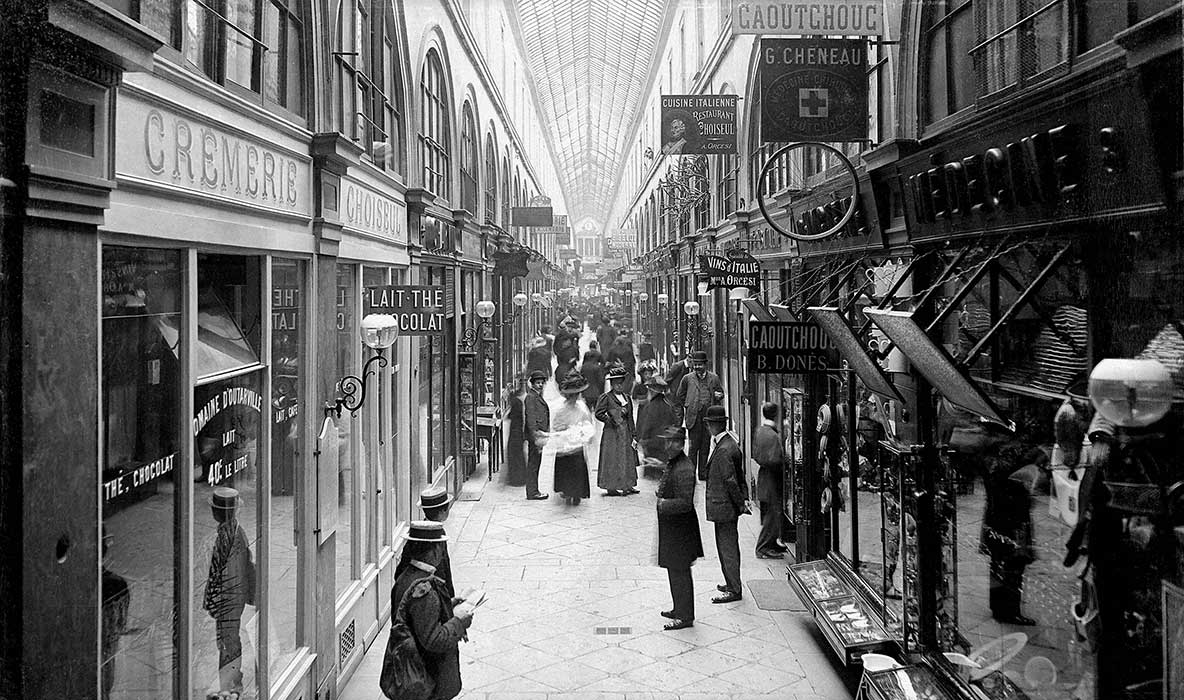

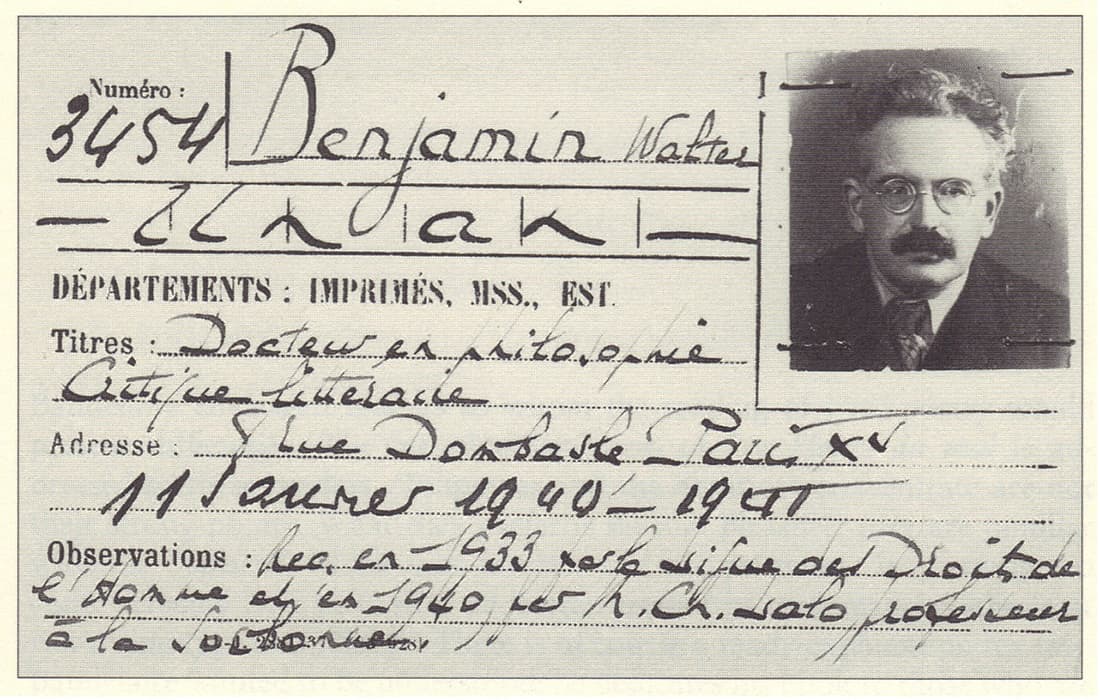

The German Jewish writer Walter Benjamin (1892–1940), one of the most important philosophers and cultural critics of the twentieth century, began The Arcades Project in 1927 as a short piece about Paris’s nineteenth-century iron-and-glass vaulted shopping passages. With their labyrinthine architecture and surrealistic juxtapositions of disparate objects and people, past and present, the arcades offered an ideal prism through which to examine the era’s capitalist metropolis and the phenomenon of modernity that had its origins there. Benjamin worked extensively on his manuscript, which grew into a sprawling compendium of quotations, reflections, and notes. When he was forced to flee Paris to escape Nazi persecution, he entrusted it to his friend Georges Bataille. Some years after Benjamin’s untimely death, the text was discovered and published.

The Arcades: Contemporary Art and Walter Benjamin will explore The Arcades Project and its ongoing relevance through works of contemporary art representing the subjects of each of the book’s thirty-six chapters. The exhibition will combine archival material from the Walter Benjamin archive in Berlin, architectural models, and artwork to evoke the elaborate structure of Benjamin’s text.

Transposing Benjamin’s arcades to the galleries of the Museum, the exhibition invites the visitor to take on the role of the flâneur, the archetypal leisured city dweller who strolled through Paris at ease, coolly attentive and open to happenstance. In addition to traditional wall labels, the poet Kenneth Goldsmith will annotate each work with appropriated texts, extending Benjamin’s reflection on Paris as the capital of the nineteenth century into New York as the capital of the twentieth.

Participating Artists

Erica Baum

Walead Beshty

Milena Bonilla

Andrea Bowers

Nicholas Buffon

Chris Burden

Haris Epaminonda and Daniel Gustav Cramer

Simon Evans

Walker Evans

Claire Fontaine

Lee Friedlander

Rodney Graham

Andreas Gursky

Raymond Hains

Pierre Huyghe

Voluspa Jarpa

Jesper Just

Sanya Kantarovsky

Mike Kelley

Tim Lee

Jorge Macchi

Adam Pendleton

Martín Ramírez

Bill Rauhauser

Mary Reid Kelley

Ry Rocklen

Markus Schinwald

Collier Schorr

Cindy Sherman

Taryn Simon

Joel Sternfeld

Mungo Thomson

Timm Ulrichs

Guido van der Werve

James Welling

Cerith Wyn Evans

The Arcades: Contemporary Art and Walter Benjamin is curated by Jens Hoffmann, Director of Special Exhibitions and Public Programs, The Jewish Museum, assisted by Shira Backer, Leon Levy Curatorial Associate, The Jewish Museum. The exhibition and its accompanying publication have been designed by Project Projects.

In the Press

“Free movement in a world overflowing with merchandise—how to manage it, how the images we take in change us—is a challenge at the heart of the Jewish Museum’s ambitious show.”

— The New Yorker

“like a good book: It takes time and a lot of reading, but the experience proves entrancing.”

— Time Out New York

“…revives Walter Benjamin’s great unfinished project, refracting his vision through the works of modern and contemporary artists.”

— Art Ltd Magazine

“The exhibit is a call to stroll through the museum and stroll through the city in a way that lets the unexpected guide us.”

— Untapped Cities

The Arcades: Contemporary Art and Walter Benjamin is made possible by the Edmond de Rothschild Foundations, the Goldie and David Blanksteen Foundation in memory of David Blanksteen, and the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts.

Additional support is provided by the Melva Bucksbaum Fund for Contemporary Art, the Barbara Horowitz Contemporary Art Fund, the Jewish Museum Centennial Exhibition Fund, Alfred J. Grunebaum & Ruth Grunebaum Sondheimer Memorial Fund, the Horace W. Goldsmith Exhibitions Endowment Fund, and the Leon Levy Foundation.

Passage Choiseul, Paris, France, c. 1910. Image provided by LL / Roger-Viollet / The Image Works

Exhibition highlights

-

Walter Benjamin’s library card

-

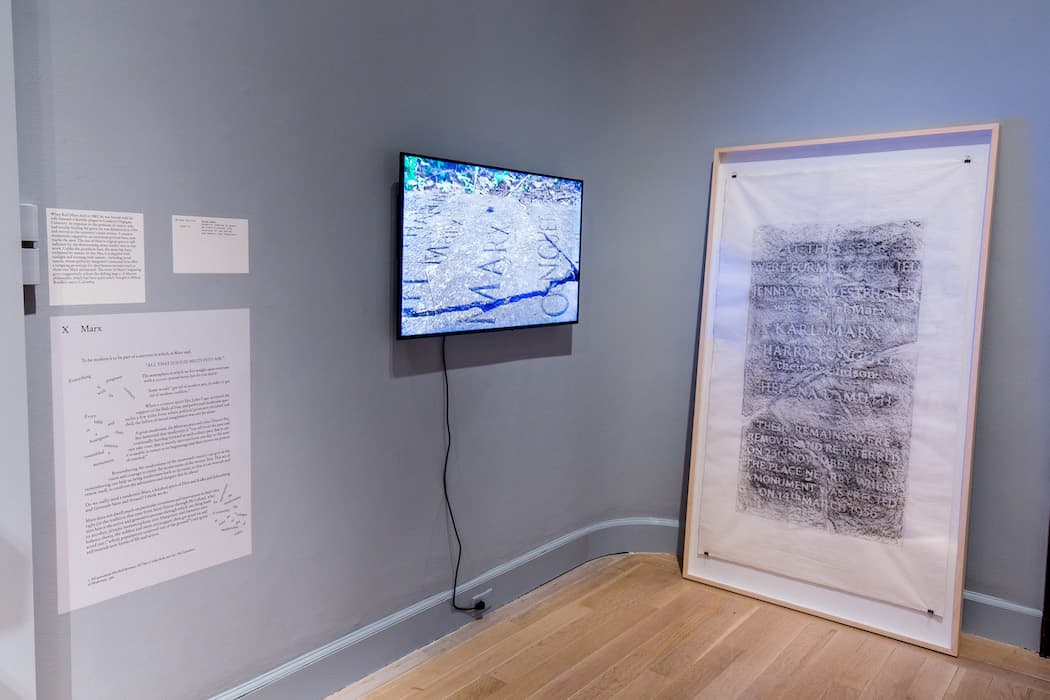

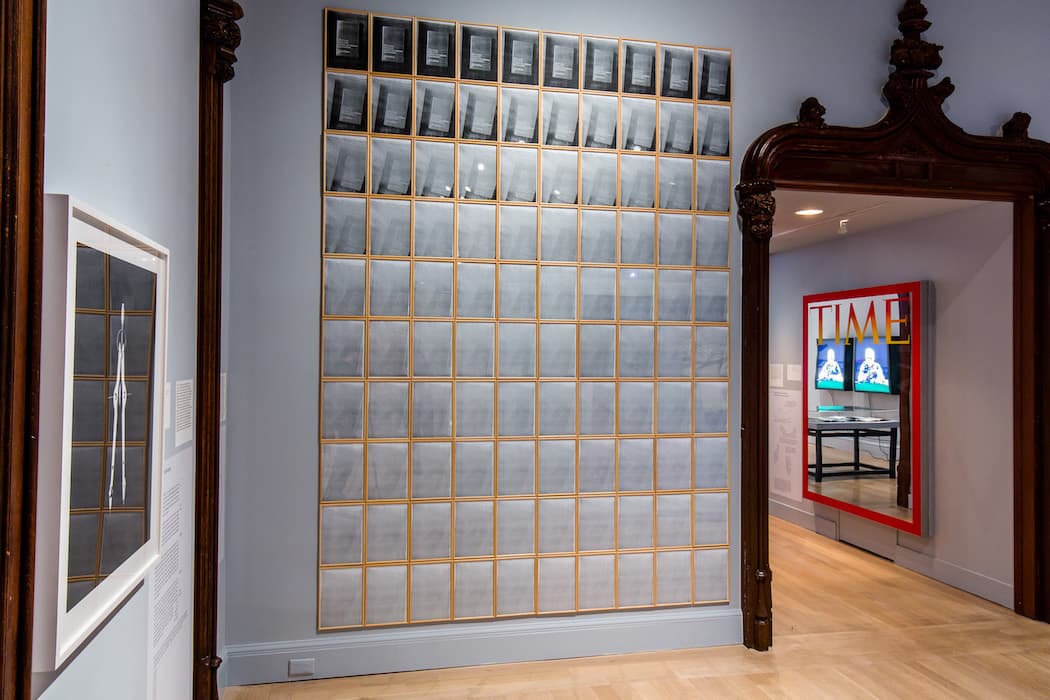

Installation view of the exhibition The Arcades: Contemporary Art and Walter Benjamin, March 17 - August 6, 2017. The Jewish Museum, NY. Photo: Will Ragozzino/SocialShutterbug.com

-

Installation view of the exhibition The Arcades: Contemporary Art and Walter Benjamin, March 17 - August 6, 2017. The Jewish Museum, NY. Photo: Will Ragozzino/SocialShutterbug.com

-

Installation view of the exhibition The Arcades: Contemporary Art and Walter Benjamin, March 17 - August 6, 2017. The Jewish Museum, NY. Photo: Will Ragozzino/SocialShutterbug.com

-

Installation view of the exhibition The Arcades: Contemporary Art and Walter Benjamin, March 17 - August 6, 2017. The Jewish Museum, NY. Photo: Will Ragozzino/SocialShutterbug.com

-

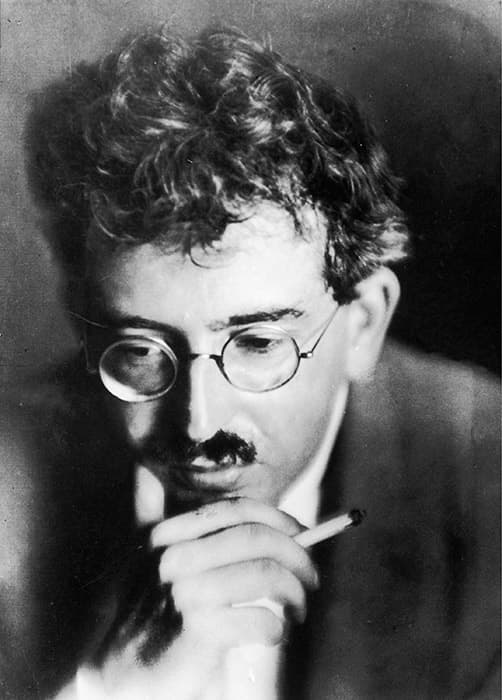

Walter Benjamin, c. 1925, photographed by Germaine Krull. Photograph © Estate of Germaine Krull, Museum Folkwang, Essen, image provided by IMAGNO / Austrian Archives, Vienna

-

Gisèle Freund, Walter Benjamin at the Bibliothèque nationale, Paris. From the series “Bibliothèque Nationale,” 1937. FND48-213-1-8A. © Gisèle Freund - RMN, image provided by IMEC, Fonds MCC, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, New York

Artworks

-

A ARCADES, MAGASINS DE NOUVEAUTÉS, SALES CLERKS Walead Beshty, American Passages, 2001–11 Slide projection Courtesy of the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles Benjamin saw the Parisian arcades, one of the subjects of Convolute A, as emblematic of a societal mindset that typified nineteenth-century Paris and, by extension, modernity as a whole. Today’s shopping mall, the heir of the arcade, is equally emblematic of the cultural milieu that produced it—namely, the car—commuting suburbs that proliferated across America in the twentieth century. By the time Benjamin began to compile his text, many of the hundreds of arcades that once dotted Paris had been destroyed, and those that remained were dilapidated. Walead Beshty’s melancholic photographs of abandoned shopping malls suggest the decline of a way of life.

-

B FASHION Collier Schorr, Jennifer (Head), 2002-14. Pigment print Private collection This image encapsulates all of the stereotypical features of woman as an object of desire in twentieth-century mass media: teased blond hair, dramatic cheekbones, lips breathlessly parted. The model’s conformity to the ideal is so perfect that it is deadening. It is all but impossible to encounter her as a real person. Collier Schorr has worked as a commercial fashion photographer throughout her career, and she often makes use of the conventions of that genre in projects that explore the ways fashion traffics in desire. Walter Benjamin saw this desire as a perverse aspect of the fetishistic worship of commodities. For bourgeois Parisians of the nineteenth century, the ever-shifting shapes of shirt collars and bustles, on view in the shop windows of the arcades, were enthralling, an exaltation of the material world. In fashion, the reduction of human beings to capitalist objects found its purest expression.

-

C ANCIENT PARIS, CATACOMBS, DEMOLITIONS, DECLINE OF PARIS Jesper Just, Intercourses, 2013 Modified 5-channel video installation Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Perrotin, New York In The Arcades Project, Walter Benjamin both describes and contributes to the mythology of Paris. He reflects on the astonishing volume of writing that has been devoted to “the investigation of this tiny spot on the earth’s surface,” from its buried antiquities to its bordellos. Jesper Just’s video records a recent contribution to this history of fascination: a residential development in suburban China wth mansard-roofed apartment blocks, a mini Champs-Elysées, and a copy of the Eiffel Tower. Though it was intended to house ten thousand people, the cheaply built replica city is sparsely populated and already crumbling. Staircases lead to fields strewn with construction debris; weeds surround the Eiffel Tower. This hard-luck doppelgänger fulfills dystopian fantasies of the demise of a great city.

-

D BOREDOM, ETERNAL RETURN Guido van der Werve, Nummer dertien, effugio C: you’re always only half a day away, 2011 12-hour HD video, framed text Courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York Many of Guido van der Werve’s performance-based films involve feats of endurance. Here, van der Werve runs around his house in Finland for twelve continuous hours on the longest day of the year, beginning at 11:00 pm and ending at 11:00 the next morning. While our attention may wander to the scudding clouds, to the light falling on foliage, to the rhythmic sound of footsteps, the runner is trapped in his loop until his self-imposed term elapses. For Benjamin, the idea of a universe of infinite repetitions without any finale or goal, was a counterpoint to the Enlightenment’s faith in progress.

-

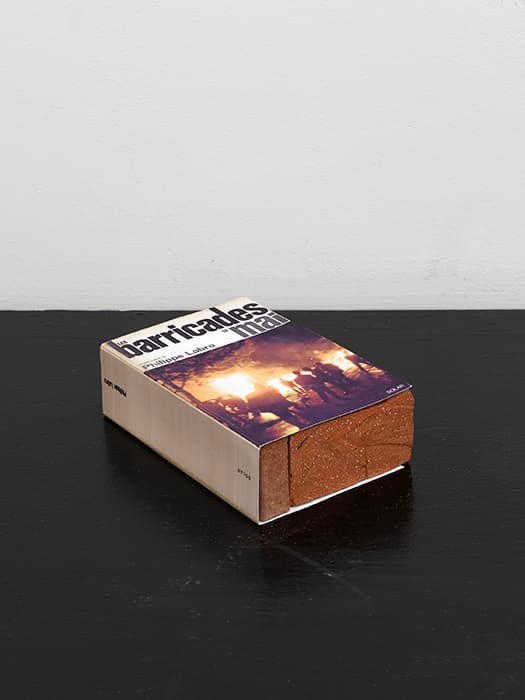

E HAUSSMANNIZATION, BARRICADE FIGHTING Claire Fontaine, Les barricades de mai brickbat, 2007 Brick, brick fragments, digital print Courtesy of the artist The period between 1830 and 1848 saw seven armed popular uprisings in Paris, with insurgents repeatedly building barricades in the city’s narrow medieval streets. In an effort to safeguard against future rebellions and to improve sanitation, the government of Napoléon III commissioned Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann to modernize the center of Paris. Haussmann transformed the city, carving wide, straight boulevards through its tangled heart. Still, Paris remained a hotbed of revolution. The Communards seized control of parts of the city in 1871; in May 1968, more than a century after Haussmann’s intervention, students and workers built their own barricades during strikes and sit-ins against the conservative government of Charles de Gaulle. Claire Fontaine’s brickbats refer to such protests, wrapping the classic street weapon in the jacket of a book. The work calls into question the maxim that the pen is mightier than the sword, giving physical form to the debate between political movements based on intellectual persuasion and those that rely on direct action.

-

F IRON CONSTRUCTION Chris Burden, Tower of London Bridge, 2003 Stainless-steel Mysto Type I Erector parts, gearbox, wood base Courtesy of The Chris Burden Estate and Gagosian Innovations in the production of iron in the eighteenth century helped to bring about the Industrial Revolution. Cast iron was light and strong; its use in bridges, buildings, and machines altered architecture and engineering, making cities taller and architecture airier—as exemplified by the Eiffel Tower, built in 1889, and glass-vaulted arcades. Walter Benjamin suggests in Convolute F that iron construction represented a turn in the history of architecture in which the technical properties of a material began to dictate the styles of buildings, rather than the reverse. Chris Burden’s bridges evoke the giddy sense of possibility in the early days of iron construction. He uses children’s building sets to represent real and imagined architecture, often at a scale that children can only dream of.

-

G EXHIBITIONS, ADVERTISING, GRANDVILLE Raymond Hains, Martini, 1968 Plexiglas relief Estate of Raymond Hains, courtesy of Galerie Max Hetzler, Paris and Berlin The Marxist concept of commodity fetishism describes the way in which, under capitalism, objects become unmoored from their relationships to real human needs and acquire an almost magical power to command desire. In nineteenth-century Paris this commercial culture was clamorous: advertisers jockeyed for the attention of potential buyers, papering over one another’s advertisements before the glue could dry. The advertising poster, a form that developed rapidly during this time, helped to produce the fetish character of the products it depicted. In this work, Raymond Hains distorts a famous logo, referring unmistakably to the Italian vermouth but undermining the effect of the original with a disorienting twist.

-

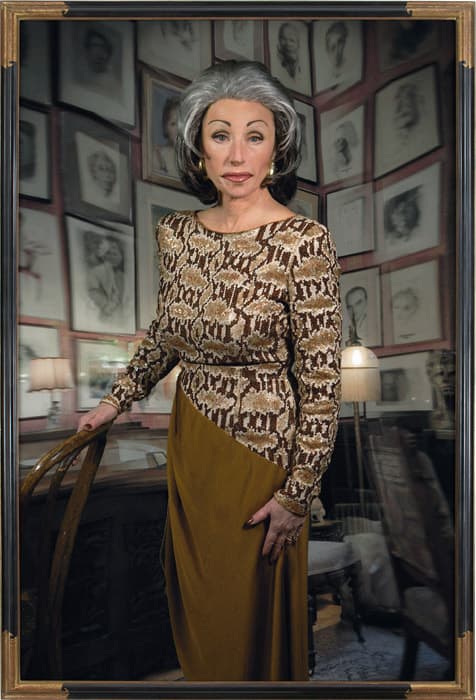

H THE COLLECTOR Cindy Sherman, Untitled #474, 2008 Chromogenic print Collection of Cynthia and Abe Steinberger Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York Benjamin views the flâneur, the gambler, and the collector as emblematic of certain aspects of modern culture. The impulse to collect is an intensified version of the general tendency of the bourgeois citizen to focus on his or her private domestic space, filling it with carefully chosen objects. In The Arcades Project, Benjamin uses a similar approach to the writing of history, which he describes as ragpicking: he recovers cast-off scraps of information overlooked by historians, weaving them into a text that illuminates a place and time. While the ragpicker gathers the detritus of society and is subject, decisively, to chance, the impetus of the collector is to shape a small world whose contents are entirely within her or his control. Cindy Sherman’s imaginary collector, portrayed by the artist herself, is ensconced in her study, her chosen objects towering behind her like fortifications. Despite this, like many of Sherman’s characters, she emanates vulnerability.

-

I THE INTERIOR, THE TRACE Simon Evans, The Voice, 2010 Mixed media on paper Collection of Alka and Ravin Agrawal Simon Evans’s drawings, made with delicate, humble materials—paper, pencil, tape, correction fluid—offer a sense of intimacy that is earnest and ironic by turns. Evans uses highly public visual formats such as subway maps and album covers to record emptyings of pockets and closets, amorous confessions, and uncomfortable memories. The Voice recalls a therapist’s injunction to “listen to the voice within.” The mandala shape of the drawing reinforces the idea that it is intended to focus attention; through thousands of mantralike iterations, however, the voice refers only to itself; it leads nowhere. Benjamin observed that under industrial capitalism the citizen is reduced to the traces she or he leaves in the administrative apparatuses of the state or the marketplace: stamps in a passport, deposits and withdrawals at the bank. Conversely, as if to offset this diminution, domestic interiors assume great importance, filled with lovingly chosen objects that reflect their owner’s personality. In a public space, the traces that the individual leaves are soon effaced or distorted by the traces left by others. At home, we are surrounded by our own marks, our own memories.

-

J BAUDELAIRE Mary Reid Kelley, Charles Baudelaire, 2015 Pigment print Courtesy of the artist and Kadist, San Francisco Mary Reid Kelley’s interest in nineteenth-century Paris derives from her sense that certain elements of its culture and politics rhyme with those of our present moment: disillusionment in the wake of failed ideals, narcissistic obsession with appearances, relentless pursuit of money. Charles Baudelaire—denounced in his time for his transgressive sensibilities—emerged as the preeminent poet of nineteenth-century Paris. His interests in vice, in crowds, and in fashion converged in lyric poetry on the beauty of the modern city. For Benjamin, Baudelaire was the perfect flâneur and chronicler of modernity; nearly a fifth of the text of The Arcades Project is devoted to the Convolute on him.

-

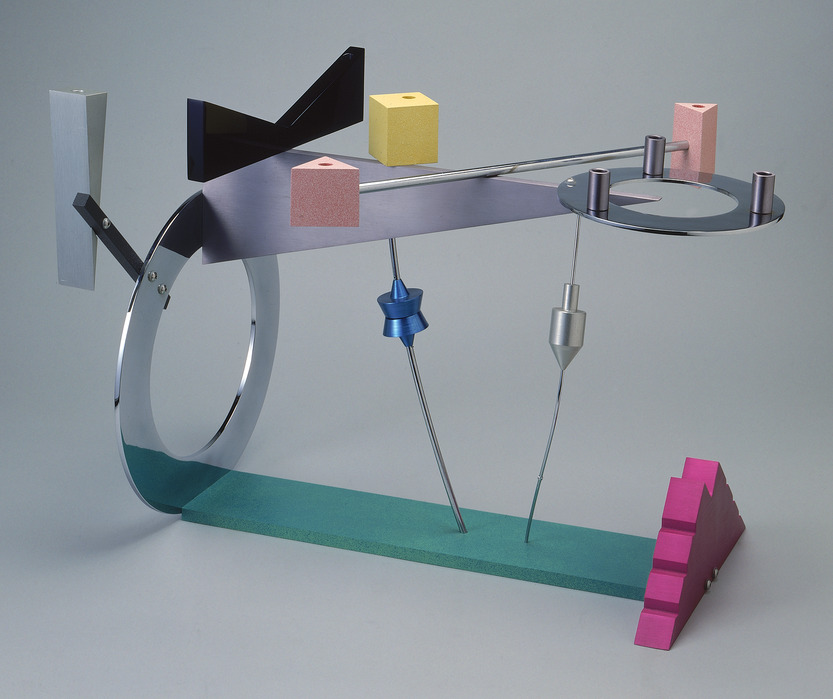

K DREAM CITY AND DREAM HOUSE, DREAMS OF THE FUTURE, ANTHROPOLOGICAL NIHILISM, JUNG Mike Kelley, Mobile Homestead Swag Lamp, 2010–13 Aluminum, steel, lighting fixtures, wiring Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts and Museum of Contemporary Art, Detroit In The Arcades Project Walter Benjamin challenges the notion that the past is a fixed object, waiting to be elucidated. He calls the present “a waking world, a world to which that dream we name the past refers.” The dream quality of the past suggests that it is mutable, a patchwork of images and symbols that can be understood in myriad ways. Mike Kelley’s work has also focused on the unreliability of memory. His project Mobile Homestead, a full-scale reproduction of his suburban childhood home, resides on the grounds of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Detroit. The building’s first floor maintains the floor plan of the original; its multilevel basement, closed to the public, includes crawl spaces and rooms that can only be accessed through ceiling hatches. The dreamlike, labyrinthine architecture suggests the slipperiness of the past. Kelley explores the denial of uncomfortable realities of abuse and oppression in domestic life, not in tune with the American Dream as represented by the suburban home, with its white picket fence. This lamp, a miniaturized version of the building, adds another layer of surrealness to the house.

-

L DREAM HOUSE, MUSEUM, SPA James Welling, Morgan Great Hall, 2014 Inkjet print Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Purchased through a gift from Nancy D. Grover in honor of Robinson A. Grover (1936–2015) Artwork © James Welling, courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles and David Zwirner, New York / London The phrase “dream house” appears in two of Walter Benjamin’s Convolutes, K and L, referring to both private dwellings and public spaces. A home may reveal the values, aspirations, and tastes of its owners; public spaces such as casinos, arcades, and museums reflect the psychology of whole societies. This work by James Welling shows the interior of the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut, founded in the mid-nineteenth century. Such institutions, a mix of museum, library, and historical society, represented the cultural aspirations and civic ambitions of American cities at the time. Today, museums like the Wadsworth shape our visions of the past; the overlaid photographic images in this piece suggest the recursive nature of this project, in which each generation reflects on and sees itself reflected in those that have come before.

-

M THE FLANEUR Lee Friedlander, New York City, 2009-2011 Gelatin silver prints Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco The figure of the flâneur, or idler, turns up frequently in nineteenth-century French art and literature. Enthralled by the city and endowed with ample leisure time, the flâneur made a study of Paris’s new boulevards, teeming with omnibuses, cafés, and shops. The shopping arcades were one of the flâneur’s favorite habitats; Lee Friedlander depicts similar spaces in New York City, the capital of the twentieth century.

-

N ON THE THEORY OF KNOWLEDGE, THEORY OF PROGRESS Taryn Simon, Folder: Swimming Pools, 2012 Archival inkjet print Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian The source material for these works comes from the Picture Collection of the New York Public Library, arranged in categories of the artist’s choosing. The library’s image bank, which comprises some 1.29 million pieces, organized under twelve thousand subject headings, is a grab bag of postcards, prints, posters, and pictures clipped from books and magazines; in it, masterworks of art appear alongside travel brochures. Certain types of images predominate, attesting to the history of the collection’s development, from bulk donations to the shifting interests of librarians and library patrons. As Taryn Simon’s work suggests, bias and happenstance contribute to the formation of ideas, and both can be informative, reflecting the society that created the archive. Both the Picture Collection and her investigation of it are Benjaminian in spirit: The Arcades Project, according to its author, aims to illuminate history through analysis of “the smallest and most precisely cut components” of the past.

-

O PROSTITUTION, GAMBLING Rodney Graham, Good Hand Bad Hand, 2010 Painted aluminum lightboxes, chromogenic transparencies Courtesy of the artist and Kadist, San Francisco Rodney Graham often appears as a character in his own work, particularly in vignettes of masculine archetypes—the marooned pirate, the soulful cowboy, the grizzled card shark. The photographs, with their slightly hokey settings and costumes, have a downbeat, self-deprecating humor. Walter Benjamin charted the ways in which capitalism strips us of the ability to determine our own fate, leaving us subject to impersonal forces whose scope and operations remain beyond our ken. The sense that success and failure arise from “causes that are unanticipated, generally unintelligible, and seemingly dependent on chance” predisposes us to gambling, whether in casinos or on the stock exchange.

-

P THE STREETS OF PARIS Jorge Macchi, The City of Light, 2007 Lamp, table, map, digital print on paper Inhotim Collection, Brumadinho, Brazil Maps are among Jorge Macchi’s favorite materials: he has charted urban itineraries that correspond to the branching cracks in a pane of glass; surgically cut away all elements of a city but its streets, rivers, or cemeteries; and used countries as collage elements, overlapping haphazardly as if fallen across a page. Benjamin was fascinated by the tangled labyrinth of Paris streets, the subject of Convolute P. The unexpected constellations of people, places, historical events, and phrases that give their names to the old city’s streets represent the chaotic plenitude of its history, enticing the adventurous flâneur.

-

Q PANORAMA Nicholas Buffon, The Stonewall Inn, 2017; Katz’s Delicatessen, 2017; Odessa, 2016; Lower East Side Coffee Shop, 2016 Foam, glue, paper, paint Courtesy of the artist and Callicoon Fine Arts, New York The original purpose of Paris’s covered shopping passages was to preserve shoppers from the dirt and disorder of the streets: from hanging laundry, cooking smells, stray animals, foul weather, and the general cacophony of urban life. They were idealized microcosms of the city. The nineteenth-century panorama was another kind of artificial, miniaturized environment, a precursor of the cinema. A typical panorama was a cylindrical room whose interior walls were lined with theatrically lit paintings and sculptures depicting a scene: a historic battle, an exotic jungle, the depths of the sea. Walter Benjamin saw the panorama as a self-contained world within a world. Nicholas Buffon’s dioramas pay homage to contemporary American cities by replicating with minute accuracy the most mundane aspects of the urban environment—parking meters and fire hydrants, air-conditioning units and delivery trucks, drooping houseplants and crushed milk cartons. They are panoramas of the unspectacular: instead of offering escape to a faraway place or time, they radiate tenderness for the careworn, disheveled places in which we live.

-

R MIRRORS Mungo Thomson, June 25, 2001 (How the Universe Will End) March 6, 1995 (When Did the Universe Begin?), 2012 Enamel on low-iron mirror, poplar, anodized aluminum Courtesy of the artist and Kadist, San Francisco The arcades, with their skylight roofs and open entrances, are simultaneously indoors and outdoors. The mirrors and reflective glass windows of their shops and cafés further confuse and interweave spaces, creating a phantasmagoric atmosphere, seductive to the flâneur and reminiscent of the montagelike technique used by Walter Benjamin in The Arcades Project. Mungo Thomson playfully exploits the capacity of mirrors to befuddle perception; his reference to Time magazine extends this disorientation into a conceptual realm. Traditionally, news magazine covers have constructed history as a series of timeless flashbulb memories. This work reacts against that static tendency by casting the viewer into a disorienting mise-en-abyme, a series of infinite reflections.

-

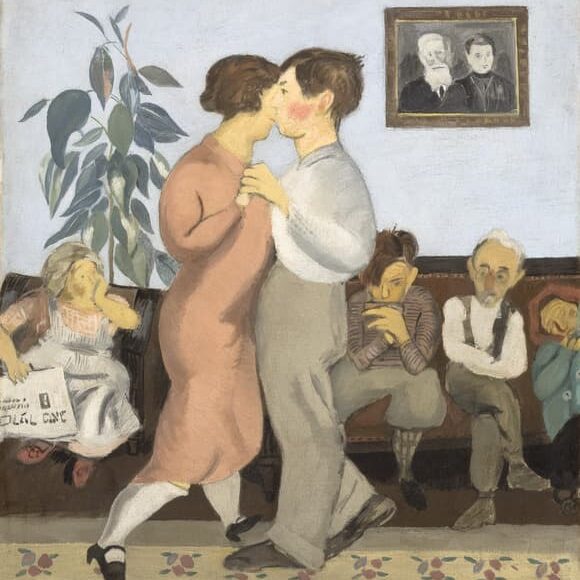

S PAINTING, JUGENDSTIL, NOVELTY Sanya Kantarovsky, Two Suns, 2017 Oil, oilstick, pastel, watercolor on canvas Courtesy of the artist When photography was invented in 1839, critics began to warn of painting’s imminent demise. In response, painting started to emphasize stylistic innovation. With Impressionism and then abstraction, inventive style emerged as a core value of what came to be called modernism. Painting survived, yet by the end of the twentieth century it appeared to have exhausted its possibilities. Nearly two centuries after the death of painting was first declared, painters continue to grapple with the concept of novelty—even if only to conclude that novelty is no longer possible. Sanya Kantarovsky ranges freely over the history of his chosen medium, imbuing his art with an uncanny sense of déjà vu.

-

T MODES OF LIGHTING Cerith Wyn Evans, Astro-photography by Siegfried Marx (1987), 2006 Chandelier (Barovier and Toso), Morse-code unit, computer Collection of Susan and Steven Jacobson, New York One of the most profound changes to the streetscape of nineteenth-century Paris was the introduction of gas lamps, which were used in the arcades as early as the 1820s; Benjamin’s sources in Convolute T describe the impact of artificial lighting on the city. In this work, an elegant chandelier blinks this text in Morse code: With the advent of radio astronomy in the early 1960s, techniques for the mapping of space made enormous technological advances. New findings were applied to existing data, and it was discovered that within maps charting vast swathe of the Southern Hemisphere, astral bodies— stimated to be millions of light years away—had been erroneously named and catalogued after microscopic inconsistencies within photographic emulsion. Solar systems identified from particles of dust, galaxies from dandruff.

-

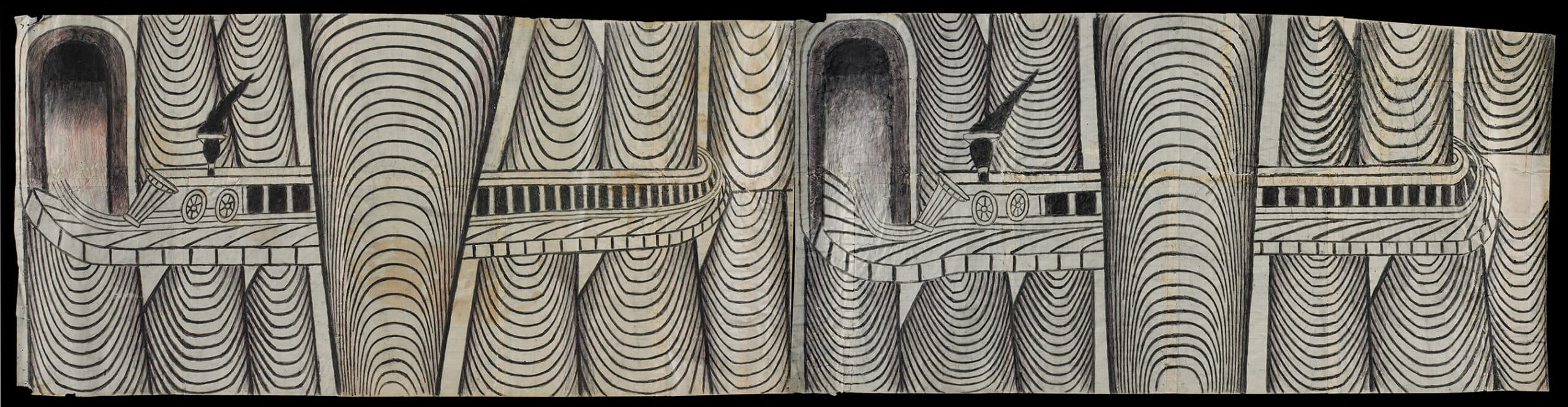

U SAINT-SIMON, RAILROADS Martín Ramírez, Untitled (Trains and Tunnels), A, B, 1960–63 Gouache, graphite on pieced paper Collection of John and Barbara Wilkerson In the nineteenth century railroads were harbingers of modernity, bringing profound change to rural and urban places alike. Railroads reached Martín Ramírez’s home in rural western Mexico eight years before his birth; as a young man he left his home in Mexico to work on railroads in the United States. Trains became a frequent subject in his drawings, weighted with cultural as well as personal significance. In Convolute U, Benjamin pairs railroads with the name of the eighteenth-century economist Henri de Saint-Simon. Saint-Simon envisioned the restructuring of society to maximize economic productivity and scientific advancement. Railroads, the machines of the new age, were the first true global network and a powerful subject for that form of productivity called art.

-

V CONSPIRACIES, COMPAGNONNAGE Voluspa Jarpa, What You See Is What It Is, 2013 Steel modules and laser-cut acrylic plates Courtesy of Mor Charpentier, Paris, Enrique Jocelyn Holt Collection, and the artist During the early years of the Cold War (1950s–1970s), art in the United States increasingly avoided overt political or social references, instead drawing the viewer’s attention to materials, colors, brushwork, and other purely visual elements. This trend culminated in Minimalist works such as Donald Judd’s iconic stacked boxes of the mid-1960s. Minimalism was given a concise motto by the painter Frank Stella: “What you see is what you see.” At the time, in Voluspa Jarpa’s homeland, Chile, a military dictatorship supported by the United States executed, tortured, and imprisoned thousands of citizens. Facing a political climate hostile to free expression, many artists couched their political critiques in indirect terms. Jarpa refers to this history, adulterating Judd’s icon with reproductions of declassified government intelligence documents. The records are so riddled with expurgations that they are nearly as inscrutable as the steel boxes that hold them. Nineteenth-century Paris saw repeated cycles of unrest and revolution, largely driven by an aggrieved proletariat responding to an entrenched aristocracy and a growing middle class. Compagnonnage, the ancient term for apprenticeship in medieval guilds, was still in operation and became a unifying mechanism of political action.

-

W FOURIER Joel Sternfeld, From the series Sweet Earth: Experimental Utopias in America, 2005 Chromogenic prints. Courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York In this series of photographs and texts, Joel Sternfeld chronicles utopian communities across the United States, from an eco-village in the Arizona dessert to a whimsical hospital in the mountains of West Virginia. Such communities have a rich history in America, the land of self-invention and fresh starts. The nineteenth-century French socialist philosopher Charles Fourier was a profound influence on such projects in both America and Europe, inspiring movements of people committed to living in ways at odds with those of mainstream society. He proposed egalitarian communities in which all members worked together and held property in common. Fourier dreamed of societies that functioned as smoothly as well-oiled machines, and the integration of domestic life with work life through architecture was one of the tenets of his vision. The unusual character of the buildings in these photographs suggests the eccentric doctrines that led to their construction.

-

X MARX Milena Bonilla Stone Deaf, 2009–10 Graphite rubbing on paper, HD video 5-minute loop Courtesy of the artist and Kadist, San Francisco When Karl Marx died in 1883, he was buried with his wife beneath a humble plaque in London’s Highgate Cemetery. In response to the petitions of visitors who had trouble finding the grave, he was disinterred in 1954 and moved to the cemetery’s main avenue. A massive monument, capped by an enormous portrait bust, now marks the spot. The site of Marx’s original grave is still indicated by the deteriorating stone marker seen in this work. Unlike the grandiose bust, the stone has been reclaimed by nature. In this film, it is dappled with sunlight and teeming with insects—including social insects, whose perfectly integrated communal lives offer a tempting prototype for ideal human societies such as those that Marx envisioned. The story of Marx’s migrating grave suggestively echoes the shifting legacy of Marxist philosophy, which has been particularly fraught in Milena Bonilla’s native Colombia.

-

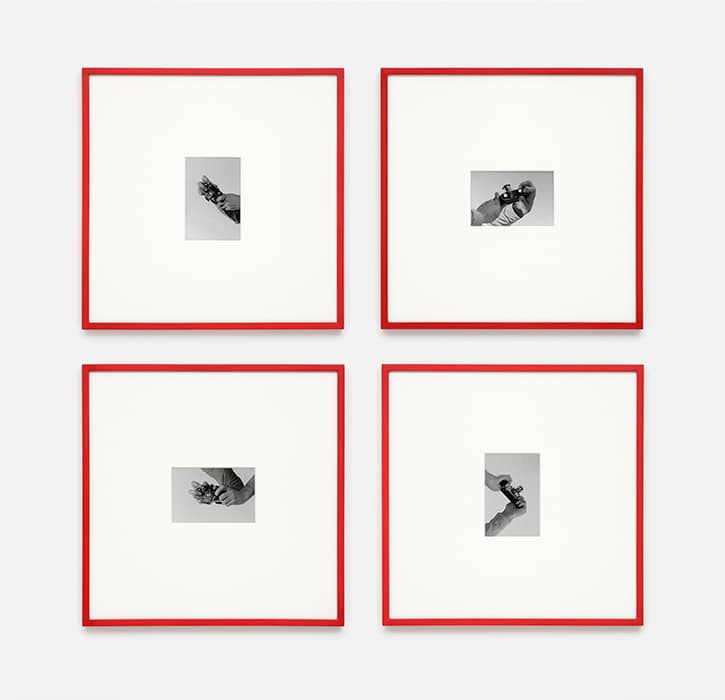

Y PHOTOGRAPHY Tim Lee, Untitled (Aleksander Rodchenko, 1928), 2008 Four photographs Courtesy of the artist and Kadist, San Francisco In the 1920s the Russian artist Alexander Rodchenko took advantage of the new, highly portable (and now-iconic) Leica 1 camera to bring his avant-garde sensibility to photography, the topic of Benjamin’s Convolute Y. His subjects were familiar—street scenes, portraits, architecture—but he introduced acrobatic angles and dynamic play with light to render them strange and exhilarating, forging dramatic abstract compositions out of ordinary objects. Putting his work in the service of the newly established Soviet Union, he made use of photography’s potential to reach the masses through inexpensive, limitless reproductions. Tim Lee has constructed an apparatus that allows the classic Leica camera to photograph itself. When photography emerged in the mid-nineteenth century, it was hailed for its ability to chronicle the world with objective exactitude. This idea, however, overlooked the intentionality of the photographer as well as variables in the photographic process. The camera lens turned back on itself is a fitting metaphor for the self-reflexive historical methodology proposed in The Arcades Project.

-

Z THE DOLL, AUTOMATION Markus Schinwald, Untitled (Machine I), 2016 Brass, wood and motor Courtesy of Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, London, Paris, and Salzburg The artificial universe of the arcades was populated by artificial beings: in shop windows, dressmakers’ dummies kept company with mechanical figures that revolved on pedestals to the accompaniment of tinkling mechanical music or popped out of closed baskets to surprise children. These uncanny dolls have a menacing aspect, suggesting the encroachment of technology and artifice on nature. Markus Schinwald blends the human with the nonhuman to unnerving effect. This figure, with its anthropomorphic Chippendale-style furniture legs, exudes an unsettling erotic energy.

-

a SOCIAL MOVEMENT Adam Pendleton, Black Dada Reader (wall work #1), 2016 Adhesive vinyl Nineteenth-century Europe was roiled by social unrest, as shifts in politics and industry led to the growing power of the working class. Alternative visions for society could be found in many forms, from utopian communes to labor unions. In contemporary America, entrenched injustices— vast disparities of wealth, enduring discrimination against members of minority groups—have recently sparked similar protest movements, from Occupy Wall Street to Black Lives Matter, as well as new writing on social conditions. Adam Pendleton’s work considers the role of language in shaping political consciousness. Here, he turns to a foundational text of black literature, W. E. B. Du Bois’s 1903 book The Souls of Black Folk, in a towering, wall-size graphic statement.

-

b: DAUMIER Walker Evans Subway Passengers, New York, 1938 Gelatin silver prints Private collection, San Francisco The French Realist painter and printmaker Honoré Daumier is known for his trenchant caricatures of the French bourgeoisie and his sympathetic portraits of members of the working class. The photographer Walker Evans, who documented the harsh conditions of poor Americans during the Depression of the 1930s, was directly influenced by Daumier. For his so-called subway portraits, taken between 1938 and 1941, he concealed a camera beneath his overcoat to capture passengers at their most unguarded. For Walter Benjamin, as for Evans, Daumier was an important link between artistic realism and the journalistic social critique of photography.

-

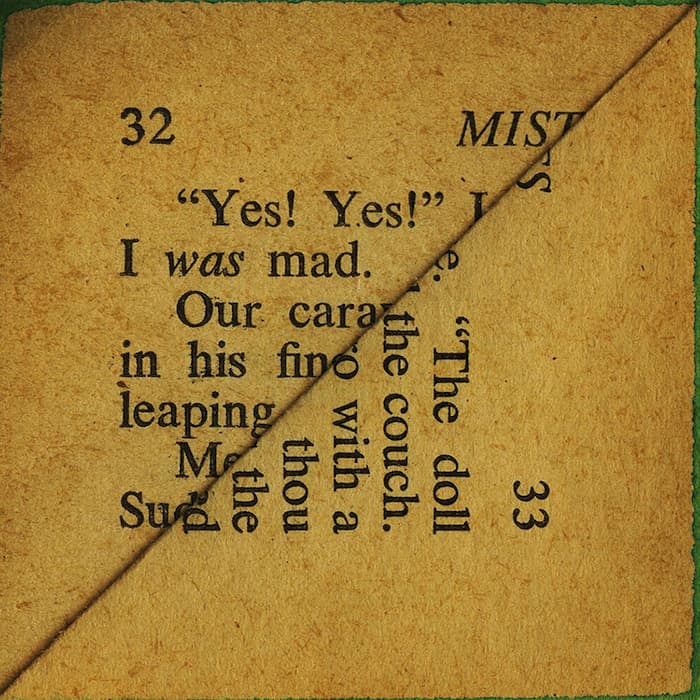

d LITERARY HISTORY, HUGO Erica Baum, From the Dog Ear series, 2009-2016 Erica Baum’s photographs explore the printed word at its most mundane and ephemeral: in pulp paperbacks, card catalogues, even the captions on stereoscopic slides. She alters these found materials to emphasize their materiality, prompting the viewer to consider the grain and color of aging paper or the tactile pleasure of thumbing through files. Dog ears, or bent page corners, are the simplest form of annotation. Here, they are presented as literary and aesthetic objects in their own right. Baum’s intervention is minimal, but the effect is profound: each dog ear hints intriguingly at the narrative obscured by the cropping of the page while also generating suggestions of new meanings. As literature, The Arcades Project is more compilation than composition. Walter Benjamin collected passages of other writers’ texts and recombined them according to his own design. In Convolute d, Benjamin explores the history of his own medium, with a focus on the popular nineteenth-century novelist Victor Hugo, whose writing was immensely politically influential. Words, for Benjamin and Baum alike, are both fragile and fiercely powerful.

-

g: THE STOCK EXCHANGE, ECONOMIC HISTORY Andreas Gursky Singapore Stock Exchange, 1997 Chromogenic print, face-mounted to acrylic Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Purchased with funds contributed by the Photography Committee, 1998 The photographs of Andreas Gursky offer a scintillating tension between abstraction and reality in all its teeming detail. A shift from the concrete to the abstract is a hallmark of late capitalist society. Money is an abstraction of value. Debt is an abstraction of money. Stocks and bonds are abstractions of abstractions, their connections to tangible things—corn to eat, wood to build houses— reduced to the buzz of binary code through fiber-optic cables. Gursky’s photographs, on the one hand, convey vividly the inhuman scale and compulsive regularity of the organs of our economy. On the other hand, they expose their own status as images, as objects, by pruning and polishing reality to a painful sheen. Benjamin saw the stock exchange as a linchpin in the collective mythology of capitalism: swarms of people, furiously busy, their inscrutable activities determining the fate of the world.

-

i REPRODUCTION TECHNOLOGY, LITHOGRAPHY Timm Ulrichs, Walter Benjamin: “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”—Interpretation: Timm Ulrichs, The Photocopy of the Photocopy of the Photocopy of the Photocopy,” 1967 Sequence of 100 black-and-white photocopies, wooden frames Courtesy of the artist and Wentrup, Berlin Though The Arcades Project was his magnum opus, Walter Benjamin is best known for his 1936 essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” Photography and film, he argued, have profoundly altered the ways in which we experience art; by allowing the dissemination of infinite copies of an image, they have divested the original of its almost magical status. Among the technologies of photomechanical reproduction, photocopy machines, in particular, prioritize efficiency over beauty, reducing clarity and detail to create serviceable replicas. Yet photocopying is an act of transformation. To create this work, Timm Ulrichs made one thousand copies of the cover of Benjamin’s essay; each successive copy was made from the one before. This display shows every tenth copy, revealing the visual noise that invades the image as the photocopy machine loses information from the original and introduces incidental details of its own, from dust on the glass to smeared ink. Thus, a purely pragmatic object is imbued with the mysterious markings of time and process that give a work of art its singular power.

-

k THE COMMUNE Andrea Bowers, The Triumph of Labor, 2016 Marker on cardboard Rennie Collection, Vancouver, British Columbia, courtesy of Susanne Vielmetter, Los Angeles Projects In 1871, working-class dissidents seized control of the government of Paris. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels cited this event as an example of the dictatorship of the proletariat, which they identified as a necessary stage in progressing from capitalism to communism. This mural is an enlarged adaptation of an 1891 woodcut by Walter Crane (1845–1915), a British artist associated with the Arts & Crafts movement, to commemorate May 1, International Workers’ Day. Crane, an ardent socialist, combined heroic depictions of workers with allegorical figures representing triumph and prosperity. Andrea Bowers reprises Crane’s composition on a monumental scale; her materials—flattened cardboard boxes and black marker—refer to the hasty, homemade signs associated with contemporary street protest.

-

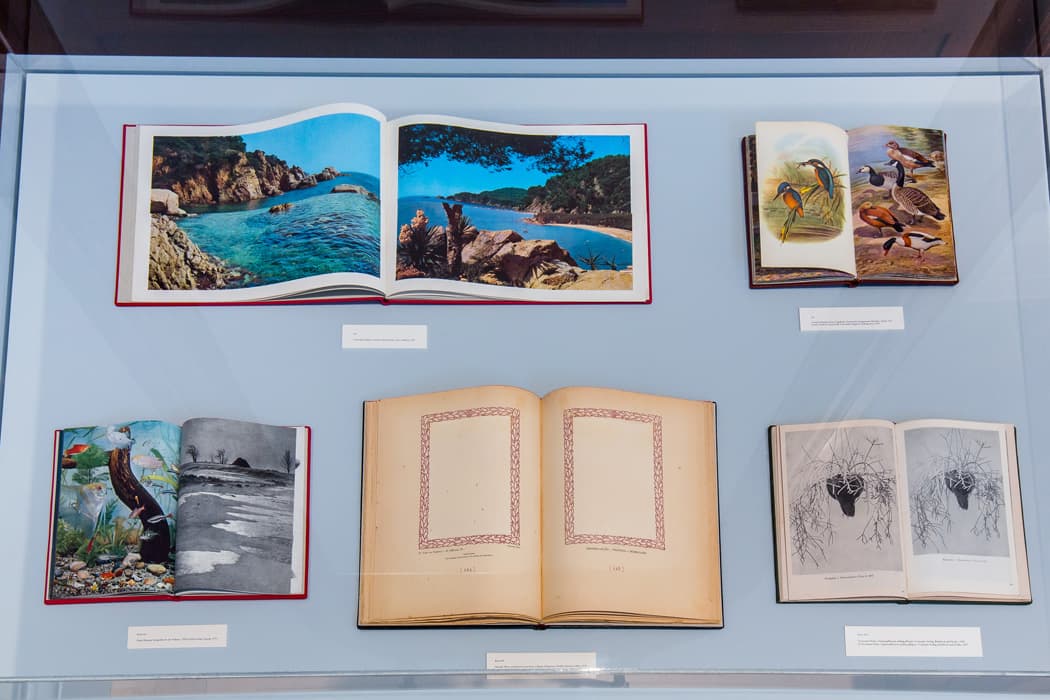

l THE SEINE, THE OLDEST PARIS Haris Epaminonda and Daniel Gustav Cramer, The Infinite Library, 2007–ongoing Reassembled and bound found books Courtesy of the artists The Infinite Library is an ongoing collaboration between Haris Epaminonda and Daniel Gustav Cramer. To create each volume in the series, the artists crop and reorder pages from existing books. In doing so, they disrupt the visual and semantic flow of the original texts: images and ideas that were once separate are brought together, and the intentions of the original authors are diverted or effaced. In Benjamin’s compilation of quotations for Convolute l, the Seine emerges as the connective tissue that binds the city of Paris together. Amid the city’s dense accretion of built structures, the river represents the enduring, elemental force of nature; a vein of unknowability, with powerful currents and murky, mysterious depths; a link to the city’s ancient past.

-

m IDLENESS Pierre Huyghe, Sleeptalking, 1998 Projection of super 16mm black-and-white film, transferred to video, sound Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York In the nineteenth century, with the rise of the bourgeoisie and changes to the lives of the working class, more and more people had time to spend outside of work and money beyond what was needed to meet basic needs. Sports, concerts, theater, and inexpensive travel all became accessible to much of the population. Leisure time, however, is defined and delimited by work time. In 1995 Pierre Huyghe founded the Association des Temps Libérés (Association of Freed Time), a gesture aimed at recovering unrestricted time. The project is aligned with Benjamin’s conception of idleness as fruitful and valuable, epitomized by the insightful, endlessly strolling flâneur. Sleeptalking blends footage from Andy Warhol’s 1963 film Sleep with a voice-over and footage of the poet John Giorno reminiscing about his life in a community of artists in New York in the 1960s and 1970s. Ribald, dreamy, and exuberant, Giorno’s rambling narrative paints a picture of a kind of utopia, inhabited by people whose art was born of idleness.

-

p ANTHROPOLOGICAL MATERIALISM, HISTORY OF SECTS Ry Rocklen, Blue Eyed Worshipper, Southern Mesopotamia, 2600-2500 B.C., 2015 Ceramic vessels, mirror-mounted panel, brass, glass Bjørnholt Collection, Oslo This sculpture is one of a series based on objects in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. It combines a photograph of an ancient figurine, printed in glaze and applied as a decal to the flat surface of the front of the sculpture, with a cast that offers a modified form of the original, again in frontal view. Rocklen sources much of the material for his art from secondhand shops and junkyards. For Blue Eyed Worshipper, he used a thrifted plush bathrobe to cast the draped tunic, while a button from one of his own sweaters became the shell and lapis lazuli eye of the figure. This process intertwines real and virtual space, the ancient and the contemporary, the authentic and the sham. Benjamin devoted Convolute p to the concept of “anthropological materialism,” his own version of the materialist, anti-idealist philosophy of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Like them, he sought explanations for the unfolding of events not in invisible or spiritual forces, but in the concrete systems and structures of the world. To this notion Benjamin added a focus on the poetic richness of everyday objects, which exert their power through their entanglement in human lives.

-

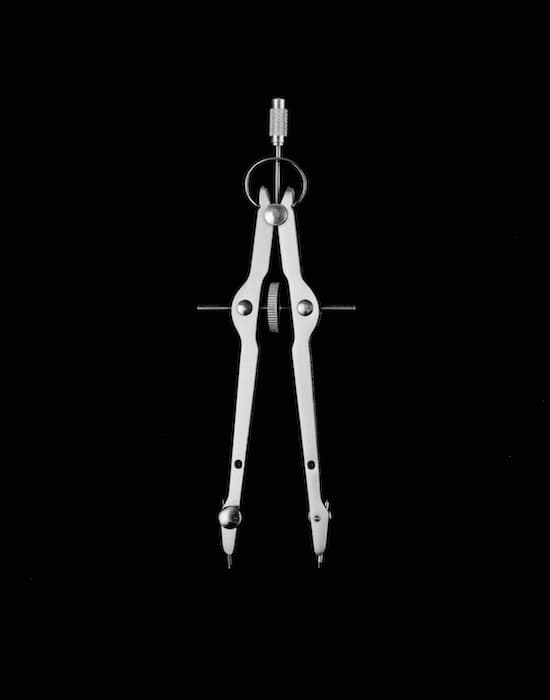

r ÉCOLE POLYTECHNIQUE Bill Rauhauser, Drawing Compass, c. 1960-1970 Pigment print Bill Rauhauser, courtesy of Hill Gallery, Birmingham, Michigan The École Polytechnique, or polytechnic school of Paris, was founded during the French Revolution in emulation of the much older art school, the École des Beaux-Arts. Benjamin, studying the Paris of the following decades, was both fascinated and worried by the shifting relationship between art and technology. If, in the past, technology had served aesthetic or spiritual ends, the nineteenth century saw it gain ascendancy over art. Bill Rauhauser began his professional life as an engineer. He is often called the flâneur of Detroit, known for his photographs of the city’s street life. This work is part of an ongoing series in which carefully selected objects appear against plain backgrounds, sharply lit so that they are visible in every detail. The shape of the compass, like the other items in the series—a music stand, a baseball, a rain boot—is dictated by its function; nevertheless, Rauhauser presents it as a thing of beauty.