The Power of Pictures: Early Soviet Photography, Early Soviet Film

From early vanguard constructivist works by Alexander Rodchenko and El Lissitzky, to the modernist images of Arkady Shaikhet and Max Penson, Soviet photographers played a pivotal role in the history of photography. Covering the period from the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution through the 1930s, this exhibition explores how early modernist photography influenced a new Soviet style while energizing and expanding the nature of the medium — and how photography, film, and poster art were later harnessed to disseminate Communist ideology. The Power of Pictures revisits this moment in history when artists acted as engines of social change and radical political engagement, so that art and politics went hand in hand.

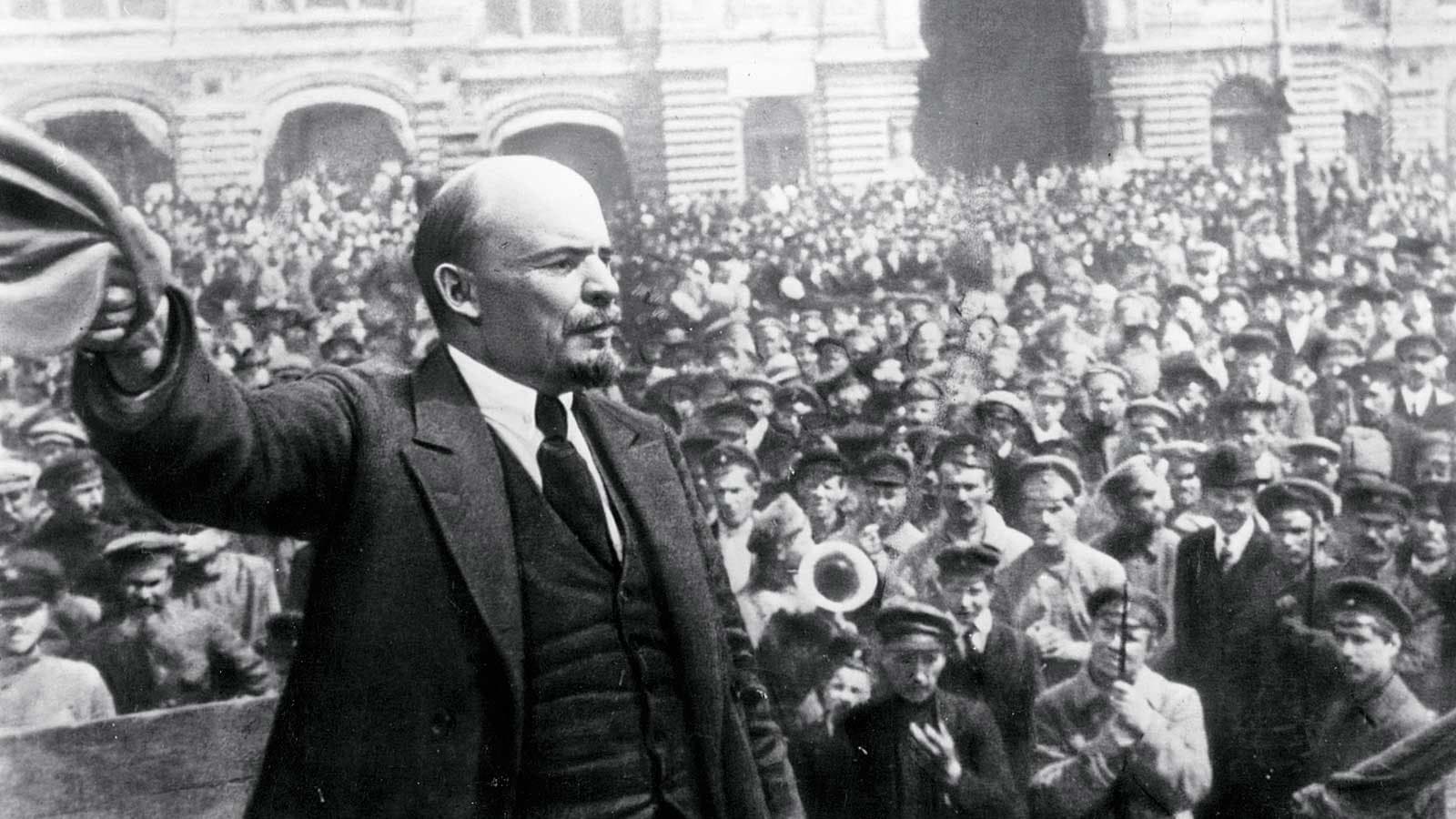

In a country where 70% of the population was illiterate, photographic propaganda often was more valuable than newspaper editorials. Lenin himself declared that the camera, as much as the gun, was an important weapon in “class struggle.” Recognizing that images had the power to transform society, Lenin put photography at the service of the Revolution — thereby serving as a historical demonstration of how artistic and political ambitions can coalesce and fortify one another. The Power of Pictures will illustrate that this work encompassed a much wider range of artistic styles and thematic content than previously recognized.

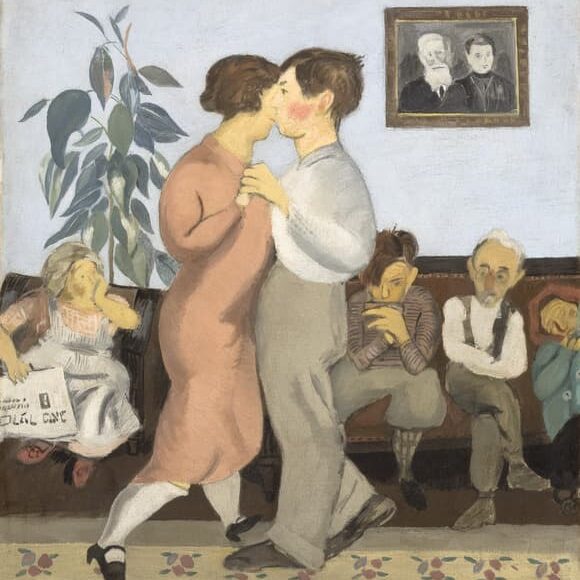

The exhibition makes clear that the artists who comprised the group Oktober, led by Alexander Rodchenko and Boris Ignatovich, and the photojournalists associated with the Russian Association of Proletarian Photographers (ROPF), such as Arkady Shaikhet and Georgi Zelma, were significantly influenced by avant-garde esthetics and by film in particular. The goal of Oktober was to create images that would force the viewer to see society in a new way, whereas ROPF — which included the majority of prominent Jewish photojournalists — championed a coherent and comprehensive documentation of reality.

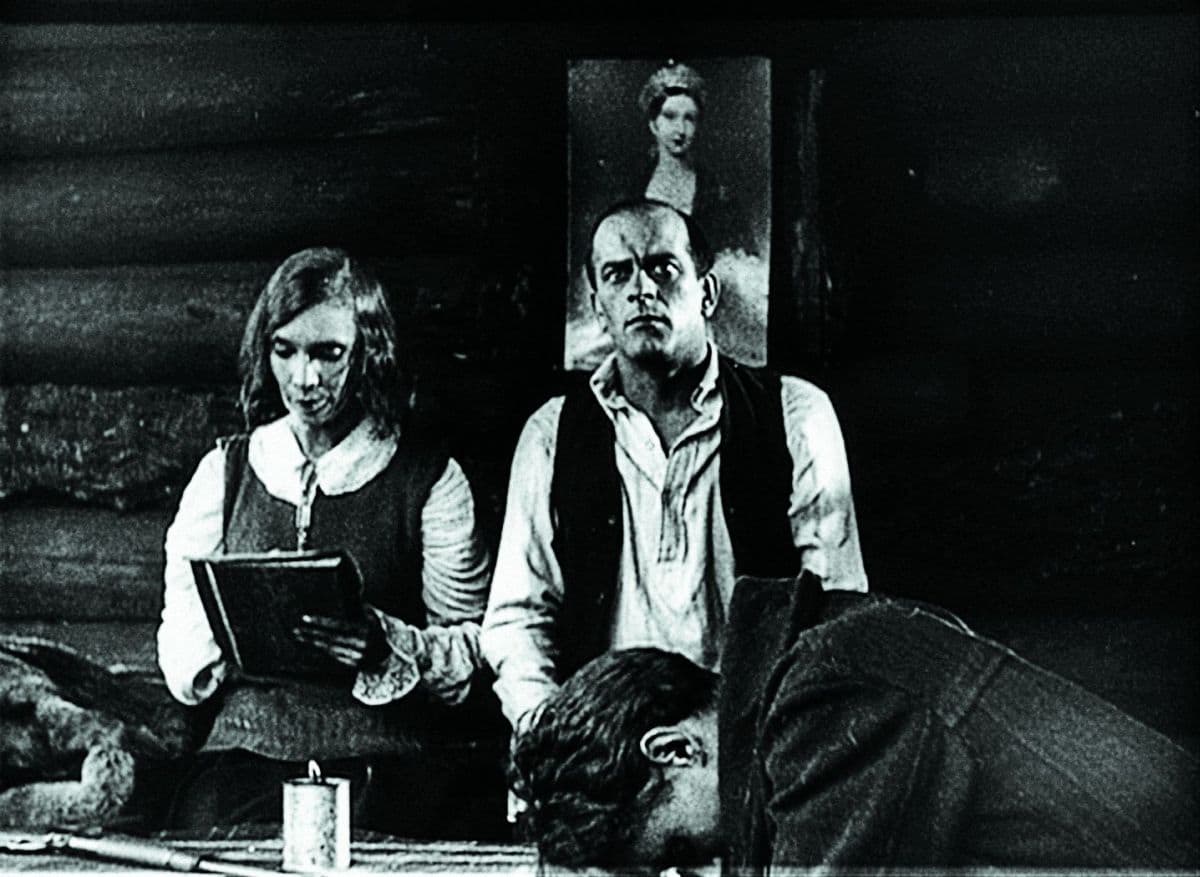

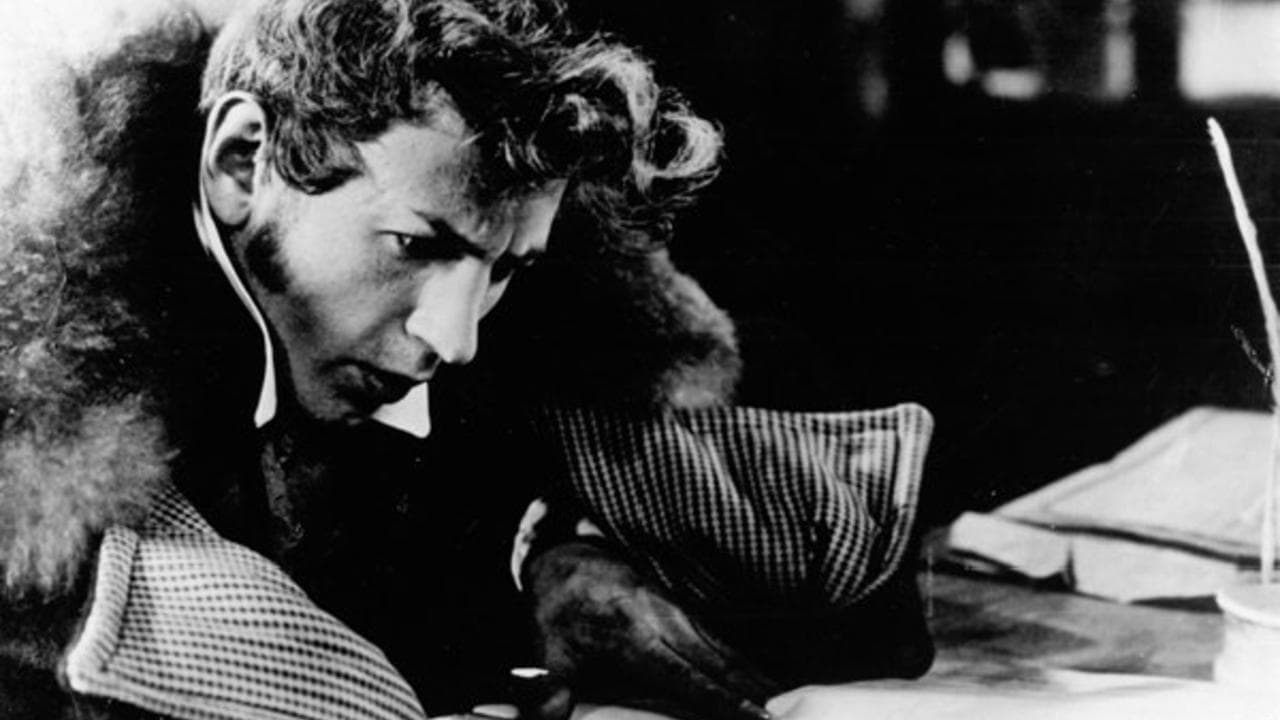

In an intimate screening room within the exhibition galleries, films by major directors of the era, including the seminal Sergei Eisenstein film Battleship Potemkin, will be shown. Despite Eisenstein’s relative fame, many of these filmmakers have been overlooked or excised from the history of the medium. More than a dozen films will be screened in their entirety on daily rotations throughout the run of the exhibition.

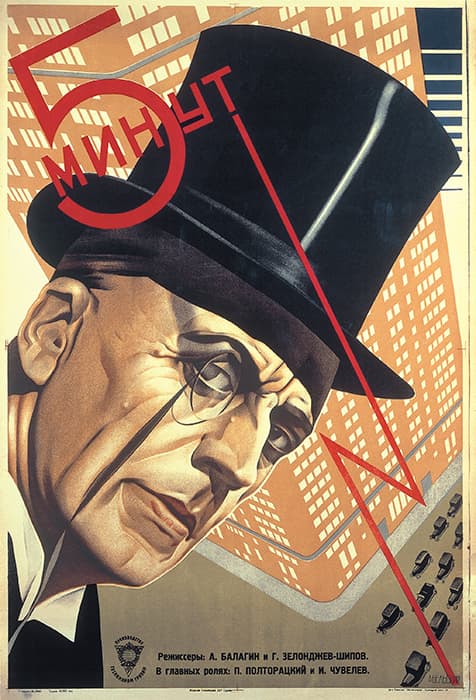

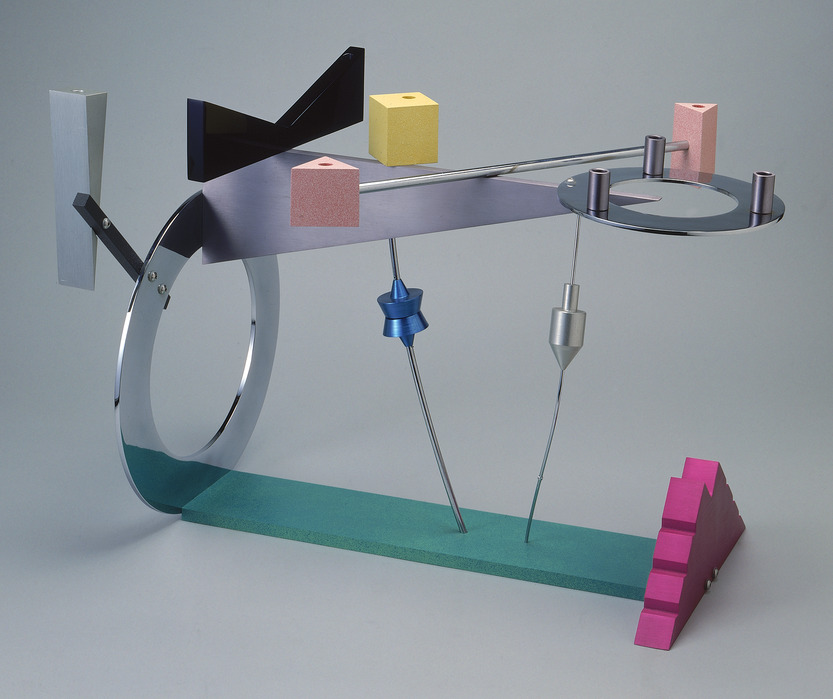

In addition to a stunning collection of photographic and cinematic works, The Power of Pictures features a rich array of film posters and vintage books that employ radical graphic styles with extreme color, dynamic geometric designs, and innovative collages and photomontages. Also presented are examples of periodicals in which major photographic works were published.

Photographers:

Boris lgnatovich

Elizaveta lgnatovich

Olga lgnatovich

Yakov Khalip

Eleazar Langman

El Lissitzky

Moisei Nappelbaum

Max Penson

Georgy Petrusov

Alexander Rodchenko

Arkady Shaikhet

Georgy Zelma

Georgy Zimin

Filmmakers:

Boris Barnet

Sergei Eisenstein

Mikhail Kalatozov

Grigory Kozintsev

Lev Kuleshov

Yakov Pratazanov

Vsevold Pudovkin

Esfir Shub

Victor Turin

Dziga Vertov

Susan Tumarkin Goodman

Senior Curator Emerita

Jens Hoffmann

Deputy Director, Exhibitions and Public Programs

In the Press

“…photography doing one of the things it does best: editing reality.”

— Holland Cotter, The New York Times

“…stunning photography from the 1920s and ’30s…showcases outstanding artistic accomplishments…”

— The Wall Street Journal

“The films…reveal the struggle between artistic invention and state control…[they] remain a testament to cinema’s radical possibilities.”

— The Wall Street Journal

Arkady Shaikhet, Express, 1939. Gelatin silver print, 15 5/8 × 21 1/8 in. (39.7 × 53.7 cm). Nailya Alexander Gallery, New York.

Exhibition highlights

Power of Pictures - The Films

Audio

The audio guide is made possible by Bloomberg Philanthropies.