Alias Man Ray: The Art of Reinvention

Alias Man Ray presents a fresh look at the diversity of Man Ray’s body of work, examining it in the context of his lifelong cover-up of his Russian-Jewish immigrant past and his suppression of his background. The project marks the first time that his willful construction of an artistic persona is explored and demonstrates how this personal agenda informs his work and methods.

The quintessential modernist, Man Ray recast the concept of artistic identity, working as a painter, photographer, sculptor, printmaker, filmmaker, poet, and essayist. He perpetually tinkered with material at hand, putting to ingenious use the practical skills learned in a variety of jobs, from advertising to mapmaking to engraving. Man Ray airbrushed paintings to make them look like photographs and exposed objects on light-sensitive paper to create cameraless “rayographs.” He met the demand for originality in the world of fashion by creating a hybrid of Surrealism and high style, and even became a celebrity himself as a portrait photographer — indeed, his fame as a photographer overshadowed his accomplishments as a painter. A conflicted identity, however, was central to an artist who yearned to escape the limitations of his Russian Jewish immigrant past.

For Man Ray, a sense of otherness was deeply connected to the problem of assimilation — the wish for both “notoriety” and “oblivion” — and hence “the desire to become a tree en espalier,” a tree trained to grow into a vine that becomes entwined with others, its origins disguised. The artist’s self-consciousness was an outgrowth of his time, a period that witnessed the rise of nation-state identity and xenophobia, and an unprecedented wave of immigration, class consciousness, and anti-Semitism. His life and work powerfully reflect his contradictory need to obscure and declare himself.

Formative Years

Born Emmanuel Radnitzky, Man Ray rejected his birth name and his family. Moving as an expatriate to Paris in 1921, he secured not just a comfortable distance from his roots but also a new status as the only American within the Parisian avant-garde. This erasure of origins precipitated the cultivation of his distinctive artistic persona — integral to his aesthetic strategies to subvert authority and deny the relationship between name and self. In changing his name from the colloquial “Manny” to the unmoored “Man,” the artist lost and found himself in anonymity.

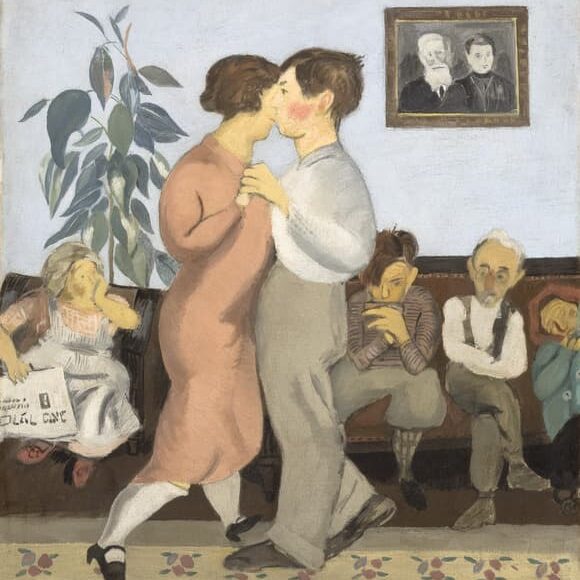

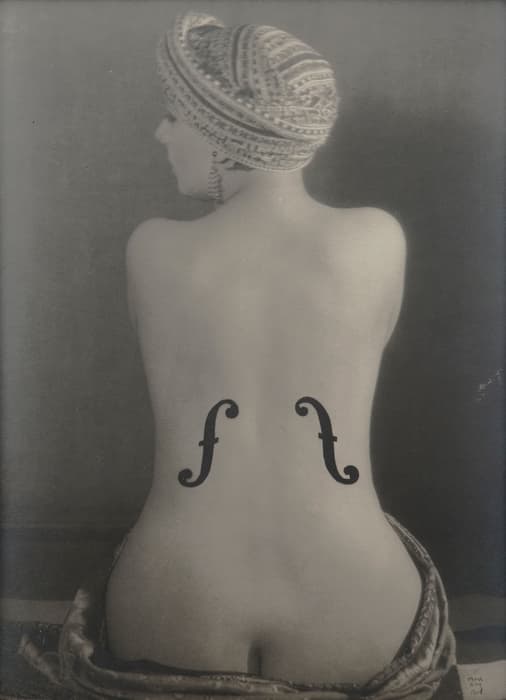

As an art student, Man Ray was stunned by the unnatural anatomy in the paintings of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, and overwhelmed by the art of the European avant-garde presented at the notorious Armory Show of 1913. In classes at the Ferrer Center, a hotbed of anarchy, Man Ray integrated social concerns with art. It was there that he learned the importance of subverting tradition to free himself from the past. Freedom, however, did not come naturally to Man Ray — as a child of Jewish immigrants, it was difficult to distance himself from Old World traditions, to carve out a geographical and psychological space within which he could create.

Shortly after the Armory Show, Man Ray moved from his family home in Brooklyn to bucolic Ridgefield, New Jersey, where artists and writers had begun to congregate. Quickly mimicking a swarm of styles, he began to assert his artistic persona, inscribing his name in the Cubist influenced Man Ray 1914. In this painting, as well as others, Man Ray accentuates the ambiguity of the relationship between figure and ground, illustrating his perhaps unconscious need to blend in with the environment — indeed, to assimilate.

Within the formal terms of two dimensions, of flatness, of shadows, Man Ray found a vocabulary to balance his desire for both notoriety and oblivion. He combined landscape and figuration to depict an abstract figure within a two-dimensional realm, as in Promenade. “Perhaps the final goal desired by the artist,” he said, “is a confusion or merging of all the arts, as things merge in real life” — an apt metaphor for assimilation. The artist’s early aesthetic strategies, and his paradoxical need to conceal and reveal himself, culminated in The Rope Dancer Accompanies Herself with Her Shadows.

Dada in New York

Man Ray’s movement toward an art of defiance positioned him perfectly to join Marcel Duchamp’s revolt against an exhausted aesthetic tradition. Together they helped initiate New York Dada, a short-lived branch of the international movement that abhorred the xenophobia throughout Europe during the Great War. By advancing the transnationalism of Dada, Man Ray became part of a riotous group that resisted any authoritative effort to reduce, define, or codify its identity.

As an anarchistic phenomenon, the eruption of Dadaism provided the perfect vehicle for Man Ray. He reveled in its spontaneous forms, which lacked specificity and programmatic direction, and in its self-mocking manifestos that required no ideological alignment. Hugo Ball, one of the founders of Dada at the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich, called for a revolt against the “senilities of grown-ups,” proclaiming that Dada aimed “to remind the world that there are independent men — beyond war and nationalism — who live for other ideals.”

With its insistence on the multiplicity of meaning, Dada facilitated Man Ray’s need to escape the insularity of his ethnicity. Having emerged in response to the anti-individual, collective experience of World War I, Dada provided Man Ray with an opportunity to practice his art within a framework to suit his need for both acceptance and independence. Dada, however, could not sustain itself in New York. As Man Ray wrote in a letter to Dadaist Tristan Tzara shortly before moving to Paris, “dada cannot live in New York. All New York is dada, and will not tolerate a rival.”

Starting Over in Paris

In 1921, Man Ray moved to Paris where he would remain for the next twenty years. There, unfettered by his past, he reinvented himself as the odd man out, the only American within a largely Parisian avant-garde. Welcomed by the Dadaists upon arrival, and later embraced by the Surrealist movement, he never fully aligned himself with either group. Unable to make a living as a painter, Man Ray began taking pictures for dress designer Paul Poiret, and soon made his name as a portraitist and fashion photographer for Vogue and Vanity Fair. His portraits of Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce, and Gertrude Stein, among others, hung on the walls of the legendary bookshop Shakespeare and Company, whose owner Sylvia Beach once wrote, “To be done by Man Ray means that you were rated as somebody.” Notably, some of his paintings began to emulate photography, a blurring of media that echoed his ongoing need to disrupt categorical thinking.

Photography was admired by the Surrealists for its “automatic” qualities and apparent freedom from artistic intent. Yet it was precisely through manipulation of the mechanical process that Man Ray declared his presence. Experimenting with techniques such as cropping, multiple exposure, solarization, and the cameraless rayograph, he demonstrated how transformable any person, object or artistic medium could be. Man Ray described himself as one who “so deforms the subject as almost to hide the identity of the original, and creates a new form.” Liberating his subjects — a contorted neck, the contours of a spring, a nude stripped of context — from fixed reality, Man Ray pushed them to the brink of metamorphosis. Likewise, in his many self-portraits made in Paris, the artist experimented with his identity as malleable and elusive.

Exiled in Hollywood

As Man Ray witnessed the rise of Fascism and the expansion of the Third Reich in Europe in the late 1930s, he at first refused to believe that he would have to leave Paris. The artist was finally forced to flee mere days before the Nazis occupied the city. He secured passage to the United States in August 1940 and, after a brief visit in New York, settled in Hollywood to wait out the war.

Many of the works Man Ray painted during this period reveal his sense of persecution. The elegance of the perfectly poised rope dancer and her shadows was replaced by a teetering figure harshly illuminated by the foreboding nocturnal sun seen in Le rebus and Night Sun — Abandoned Playground. Man Ray despised the stark, invasive light representing the relentless German advance from which one could not hide. As the artist began to lose his guarded anonymity, he was compelled to confront a part of himself — his Jewishness — that he had assiduously avoided. It was at this time that he employed the motif of the articulated manikin, symbolizing his dread of being manipulated by others. He also became preoccupied with images of masks, secrecy, and concealment—as seen in The Fortunes of the Artist’s Double and Songe de la clef.

Another formal device Man Ray returned to was the use of primary colors. In La fortune and other works created during this fearful period, Man Ray sought to denaturalize nature, to assert the primacy of art, for he believed that primary colors are man-made. “A picture done in pure spectrum colors,” Man Ray wrote, “could never be reconciled with its surroundings — it would even combat other rainbows.”

A World of His Own Making

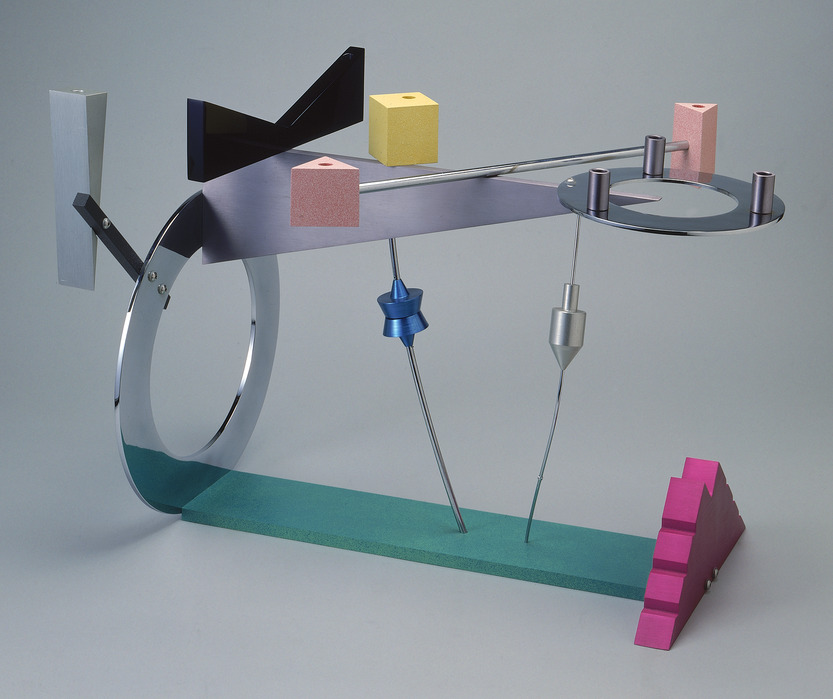

Man Ray returned to Paris with his wife Juliet in 1951, alienated from the contemporary art world and unconcerned that the epicenter of the avant-garde had shifted from Paris to New York. It was fitting that the artist, ever the outsider, would go against the grain and return to the city where he felt most comfortable, to work according to his own rules and tastes. In his new studio on rue Férou, he surrounded himself with his Surrealist “objects of affection” — such as Table for Two, Non-Euclidian Object I, and Smoking Device — whose number grew from his constant visits to the flea market, populating his environment as if they were his offspring.

The artist’s wistfulness and anxiety about being forgotten surfaced in many ways, including the writing of his memoir, Self Portrait (1963). Toward the end of his life, he returned to his youthful mechanical drawings, continuing the ceaseless transformations of earlier paintings into lithographs, and unique objects into multiples. While the title Unconcerned But Not Indifferent would become Man Ray’s epitaph, summing up his feelings about critics whom he felt misunderstood his work, what lends this collage its poignancy is its reprise of the artist’s preoccupation with shadows.

As Man Ray’s career began to falter in California and, later, in Paris, the problem of being out of sync with the art world became more pressing, and the leitmotif of the shadow assumed a new gravity. This is apparent in the screen La forêt dorée de Man Ray, an allegory of the artist’s need to obscure himself, and the elegiac La rue Férou, which pictures the rag picker of Man Ray’s youth burdened by the now-larger-than-life figure of The Enigma at the doorstep of his final studio.

In the Press

“It’s a traditional retrospective with an irresistible biographical hook, one that is both old-fashioned (dust off your Freud) and up to the minute (identity is fluid).”

— The New York Times

Alias Man Ray: The Art of Reinvention is made possible by generous grants from S. Donald Sussman and the David Berg Foundation. Major funding was also provided by the Peter Jay Sharp Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Foundation, the Leon Levy Foundation, Ellen S. Flamm, and the Lisa and John Pritzker Family Fund. Additional support was provided by the Neubauer Family Foundation Exhibition Fund and other donors.

The exhibition is sponsored by the Jerome L. Greene Foundation.

The catalogue is funded through the Dorot Foundation publications endowment.

Man Ray, Le violon d’Ingres, 1924, vintage gelatin silver print. Rosalind and Melvin Jacobs Collection © 2009 Man Ray Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris