Reclaimed: Paintings from the Collection of Jacques Goudstikker

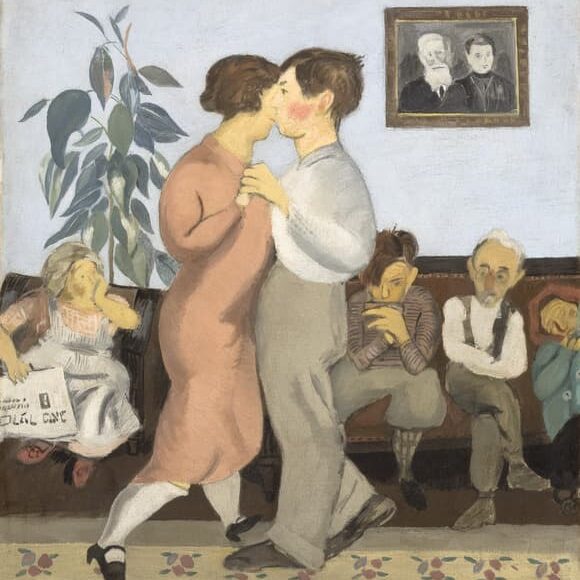

This exhibition presents rarely-seen Old Master paintings collected by Jacques Goudstikker, a prominent Jewish art dealer in Amsterdam prior to World War II. In 1940, Goudstikker was forced to flee war-torn Europe. His gallery, which contained approximately 1,400 works of art, was looted by the Nazis. Recently his family reclaimed 200 paintings from the Dutch government; the finest of these works are on view in this exhibition.

Reclaimed reveals the remarkable legacy of Jacques Goudstikker, a preeminent Jewish art dealer in Amsterdam whose vast collection of masterpieces was almost lost forever to the Nazi practice of looting cultural properties. Between the two World Wars, Goudstikker’s impressive and historically important collection rose to international acclaim. This exhibition presents rarely-seen Old Master paintings—including Dutch Old Master works and Italian and Northern Renaissance paintings—recently restituted to Goudstikker’s family.

Forced to flee the Netherlands with his family in May 1940 immediately after the Nazi invasion, Goudstikker died in a tragic accident while escaping. He left behind approximately 1,400 works of art in his gallery, the bulk of which were looted by Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring. After the war, over 200 of Goudstikker’s paintings were found by the Allies in Germany and returned to the Dutch government to be restituted to the rightful owner. Unfortunately, that was not accomplished, and they remained in the Dutch national collection.

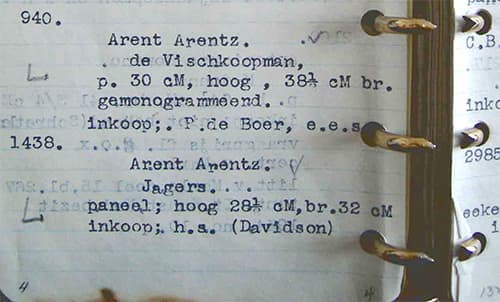

The small black notebook he used meticulously to inventory his collection was found with Goudstikker at the time of his death, and later became a crucial piece of evidence in the battle to reclaim his art. In February 2006, Goudstikker’s family successfully reclaimed 200 artworks from the Dutch government in one of the largest restitutions of Nazi-looted art.

The returned masterpieces, alongside photographs and documents relating to Goudstikker’s life, provide an intimate perspective and an opportunity to reflect on the consequences of Nazi looting. This exhibition brings to light Jacques Goudstikker’s extraordinary story and celebrates the historic restitution of the artworks to the rightful heir.

By all accounts, Jacques Goudstikker was a larger-than-life figure who helped shape the taste of his age. A born salesman and entrepreneur, he operated a grand gallery in a seventeenth-century mansion on one of Amsterdam’s prominent canals and entertained with panache at his home on the Amstel River and at his country estate, Nyenrode Castle on the Vecht River.

Born into a family of art dealers, Goudstikker was educated at the Commercial School before enrolling in art history courses at Leiden University. He also studied in Utrecht where he was introduced to a wider field of study and a more aesthetic assessment of art. Following in the steps of his grandfather and father, Goudstikker officially entered the family business in 1919, at the age of 22 and almost immediately introduced distinctive changes.

Goudstikker contributed to raising Amsterdam’s profile as an international center for the art trade and strove to develop international collectors and foster Dutch appreciation of foreign art. He expanded the gallery’s holdings and exhibitions to include not only Northern Baroque art, his specialty, but also early Northern paintings, Italian Renaissance works and later European paintings. His scholarly and elegant catalogues attest to increasingly varied international offerings and a greater ambition for the gallery and its publications.

Goudstikker developed the innovative idea of presenting thematic exhibitions such as the first survey of Dutch winter landscape paintings, and also mounted monographic exhibitions on Peter Paul Reubens and Solomon van Ruysdael. In addition he chose works for an important exhibition of Italian art at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. Christian themes are prevalent in Italian Renaissance work and Goudstikker was one of many well-known Jewish art dealers and scholars whose connoisseurship encompassed such works.

In 1937, at one of his charity banquets, entitled “Vienna on the Vecht,” he hosted the accomplished and beautiful Viennese opera singer Désirée von Halban Kurz. Goudstikker was smitten with Dési, the daughter of the famed Jewish coloratura soprano Selma Kurz, and the two soon married and had a son.

With a Nazi invasion of the Netherlands appearing inevitable in late 1939, Jacques Goudstikker applied for and was granted immigration visas to the United States for himself, his wife Dési, and their year-old son Eduard (nicknamed “Edo”). He had made some preliminary provisions for escape, sending a few pictures to England, transferring a relatively small amount of money to New York, and appointing a representative to handle his affairs in the event he was forced to flee.

The Goudstikkers’ visas expired on May 9, 1940, and the Nazi invasion of the Netherlands on the next day prevented Goudstikker from going to the U.S. consulate to obtain renewals. As German forces approached Amsterdam on May 13, the Goudstikkers gathered up a few assets and set off. Even with expired visas, they managed to find passage on the SS Bodegraven, the last cargo boat to England, in part because a soldier on guard at the port remembered seeing Dési sing for the troops. Without proper papers, however, they were not permitted to disembark once they arrived in Dover and were forced to continue on to Liverpool along with hundreds of other refugees.

While crossing the English Channel on the night of May 15, Goudstikker left the cargo ship’s cramped hold and went up on deck for air. In the blackness he fell through an uncovered hatch and was killed. Devastated, Dési was allowed ashore only long enough to make hasty arrangements for her husband’s burial in Falmouth, England. Dési and Edo traveled on to Canada before eventually settling in the United States.

Looting & Restitution

Within weeks of Goudstikker’s death, his collection of paintings, drawings, sculptures, and antiques were looted by the Nazis. Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, Adolf Hitler’s second-in-command, took approximately eight hundred of the most valuable works back to Germany, where many were displayed in his several residences. Some of the works of art not kept by Göring were given to Hitler to be placed in a museum he was planning for his hometown of Linz, Austria.

The gallery itself and Goudstikker’s country estates were transferred to Göring’s henchman Alois Miedl in a forced sale for a fraction of their value. This “sale” was imposed over Dési’s express objection, even though, after Jacques’ death, she controlled a majority of the gallery’s outstanding shares. Miedl continued to operate the gallery under the Goudstikker name throughout the war, profiting from its infrastructure, remaining stock, and respected reputation. The forced sale and looting of the Goudstikker Gallery was among the largest single acts of plundering of a significant art collection by the Nazis.

In the years immediately after the war, over two hundred paintings looted from Goudstikker’s collection were located by the Allies in Germany and returned to the Netherlands with the expectation that they would be restituted to the rightful owner. Despite Dési’s efforts to recover them, however, the Dutch government kept the works in its national collections.

During the late 1990s, new information about Nazi-looted artworks in the Dutch government’s national collection became available as part of a larger reexamination of post-war restitution practices. This inspired Jacques Goudstikker’s family to take up the task that Dési had been unable to complete and to try again to reclaim his legacy. The efforts of the family, working with a team of art historians and legal experts, culminated in the restitution of 200 artworks from the Goudstikker Collection by the Dutch government in February 2006. It is one of the largest restitutions of Nazi-looted art.

More than a thousand works have yet to be restituted, and the quest continues.

The exhibition was originally organized by Peter C. Sutton, Director and CEO of the Bruce Museum in Greenwich, Connecticut.

In the Press

“…an extraordinary, continuing tale of looting and restitution.”

— The New York Times

This exhibition is sponsored by Thomas S. Kaplan; the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany; and Herrick, Feinstein LLP.

Generous support was provided by Hanni and Peter Kaufmann; an anonymous donor in memory of Curtis Hereld; Fanya Gottesfeld Heller; Melvin R. Seiden; the Alfred J. Grunebaum Memorial Fund; Carol and Lawrence Saper; and other donors.

Online exhibition text is drawn from the exhibition catalogue, Reclaimed: Paintings from the Collection of Jacques Goudstikker, published by Yale University Press.