Chagall, Lissitzky, Malevich: The Russian Avant-Garde in Vitebsk, 1918-1922 Opens at the Jewish Museum on September 14, 2018

Exhibition Explores Extraordinary Years Following Russian October Revolution of 1917 When Vitebsk Became an Avant-Garde Art IncubatorPress Preview:Wednesday, September 12, 2018, 11:30 am to 3 pmRemarks at 12:30 pmRSVP: [email protected]

New York, NY, September 4, 2018 – The Jewish Museum will offer museum visitors a rare opportunity to explore a little-known chapter in the history of modernity and the Russian avant-garde. On view from September 14, 2018 through January 6, 2019, Chagall, Lissitzky, Malevich: The Russian Avant-Garde in Vitebsk, 1918-1922 will focus on the People’s Art School (1918-1922), founded by Marc Chagall in his native city of Vitebsk (in present day Belarus). The exhibition explores the extraordinary years following the Russian October Revolution of 1917, during which Vitebsk – a small city with a significant Jewish population – became an incubator of avant-garde art. Through nearly 160 works and documents loaned by museums in Vitebsk and Minsk and major American and European collections, the exhibition will present the artistic output of three iconic figures – Marc Chagall, El Lissitzky and Kazimir Malevich – as well as works by students and teachers of the Vitebsk school, such as Lazar Khidekel, Nikolai Suetin, Ilya Chashnik, David Yakerson, Vera Ermolaeva, and Yuri (Yehuda) Pen, among others. Chagall, Lissitzky, Malevich: The Russian Avant-Garde in Vitebsk, 1918-1922 is organized by the Centre Pompidou, Paris, in collaboration with the Jewish Museum, New York.

The year 2018 marks the 100th anniversary of Chagall’s appointment as Commissar of Arts for the Vitebsk region, a position that enabled him to carry out his idea of creating a revolutionary art school in his city, open to everyone, free of charge, and with no age restrictions. The People’s Art School was the perfect embodiment of Bolshevik values, and was approved in August 1918. A month later, Chagall was appointed Commissar of Arts. El Lissitzky and Kazimir Malevich, leading exponents of the Russian avant-garde, were two of the artists invited to teach at the school. A period of feverish artistic activity followed, turning the school into a revolutionary laboratory. Each of these three major figures sought, in his own distinctive fashion, to develop a “Leftist Art” in tune with the revolutionary emphasis on collectivism, education, and innovation. The exhibition traces the fascinating post-revolutionary years when the history of art was shaped in Vitebsk, far from Russia’s main cities.

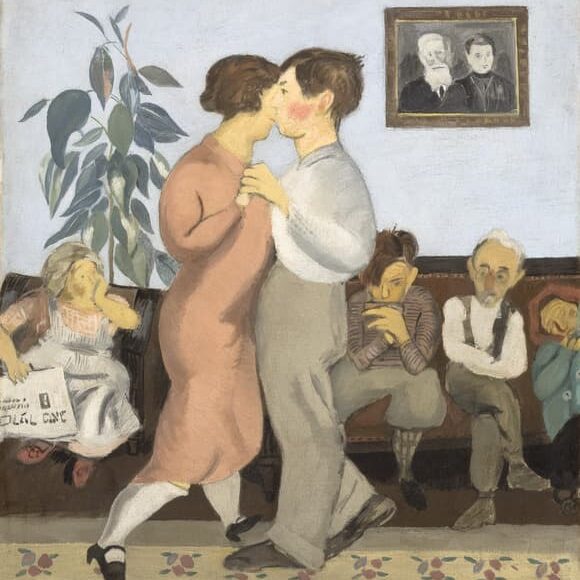

The Russian Revolution of 1917 had an enormous effect on Chagall. The passage of a law abolishing all discrimination on the basis of religion or nationality gave him, as a Jewish artist, full Russian citizenship for the first time. This inspired a series of monumental masterpieces, such as Double Portrait with Wine Glass (1917), celebrating the happiness of the newly married Chagall and his wife Bella. As the months went by, Chagall felt the need to help young residents of Vitebsk lacking an artistic education, and to support other Jews from humble backgrounds. Once he was named Commissar of Arts in his city, his first task was to organize festivities marking the first anniversary of the October Revolution. The streets of Vitebsk were transformed into a sea of colorful banners and signs designed by Chagall and David Yakerson. Studies for these banners will be on view in the exhibition. After the celebrations, Chagall devoted himself to creating his school which was officially inaugurated on January 28, 1919, with the goal of providing a high level of teaching in all art styles.

While the first teachers left before the spring, they were replaced by others. El Lissitzky took charge of the printing, graphic design, and architecture workshops. The leader of the abstract movement, Kazimir Malevich, founder of Suprematism, was a charismatic theorist who galvanized the young students upon his arrival in November 1919. He formed a group with sympathetic teachers and students called UNOVIS (Affirmers of the New Art). Suprematist abstraction became the new paradigm. Lissitzky, as a trained architect, played a crucial role in the newly founded collective. With his extraordinary Proun series (Projects for the Affirmation of the New), he was the first to extend architectural volume to the pictorial plane, considering the series as “stations where one changes from painting to architecture.” Chagall continued to produce his individualist art while making ironic use of the language of non-objective art promoted by Malevich and his students. Meanwhile, during his time in Vitebsk, Malevich began to abandon painting – an exception being his magisterial painting Suprematism of the Spirit (1919), included in the exhibition – in favor of his main theoretical writings and education. A second painting by Malevich, Mystic Suprematism (Red Cross on Black Circle), 1920-22, will also be on view. A methodical and stimulating teacher, he attracted more and more students, while attendance to Chagall’s classes gradually dwindled.

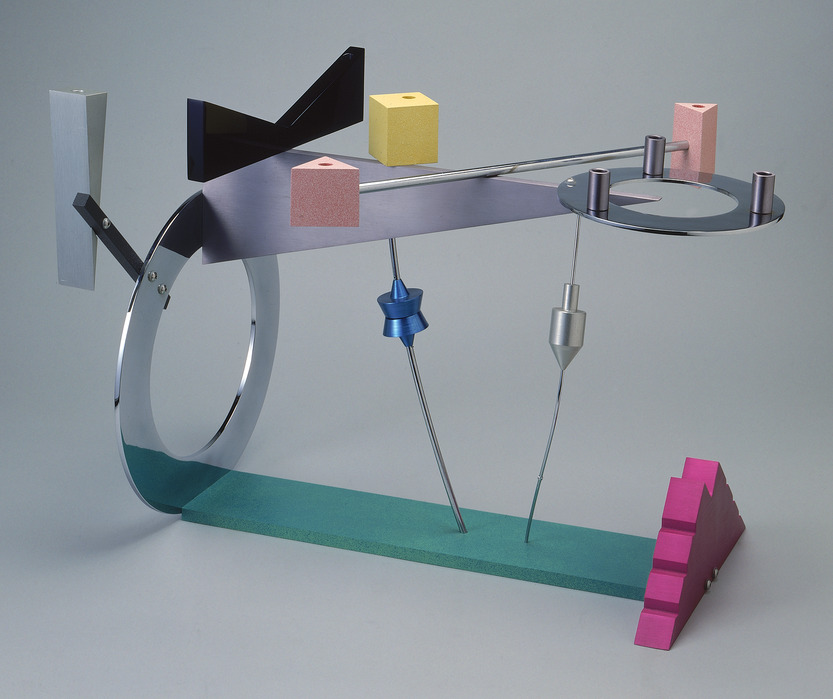

Chagall’s dream was to develop a revolutionary art independent of style or dogma but this came to an end in the spring of 1920. He decided to leave Vitebsk in June and went to live and work for the Jewish theater in Moscow. After Chagall’s departure, Malevich and the UNOVIS collective, now in command, staged exhibitions in Vitebsk and major Russian cities. With the end of civil war in 1921-1922, the political climate changed again. The Soviet authorities decided to impose ideological and social order, eliminating artistic movements which did not directly serve the interests of the Bolshevik party. In May 1922 the first graduating class of the Vitebsk school of art was also the last. During the summer, Malevich left for Petrograd (now Saint Petersburg) with several of his students, and continued to develop his ideas on volumetric Suprematism, building models of utopian architecture called Arkhitektons, and designing porcelain tableware. A number of these works will be shown in the exhibition. Moving to Berlin in 1922, Lissitzky further developed his Prouns and, later, had his first solo exhibition in Hanover.

The exhibition is divided into five sections: “Post-Revolutionary Fervor in Vitebsk,” “The People’s Art School,” “‘The New Art’: Lissitzky and Malevich,” “Collective Utopia,” and “After Vitebsk.”

The first section, “Post-Revolutionary Fervor in Vitebsk,” focuses primarily on the impact that the Russian Revolution of 1917 had on Marc Chagall. His exuberant and vibrant paintings from this period feature swinging or tilted figures – a reference to the upheavals of Russia in this epoch. Also included will be studies made by Chagall and by David Yakerson for banners to decorate the city of Vitebsk for the celebrations of the first anniversary of the Revolution.

In “The People’s Art School,” the evolution of the school, which opened in January 1919, will be traced with works by several of the key teachers and students. Keen to provide a high level of instruction in all styles, Chagall approached a diverse range of artists to join the faculty. The institution initially had 120 youths enrolled, mainly Jewish boys from working-class families. Suprematism arrived along with its founder, Kazimir Malevich, in November 1919. His ideology, which proposed an art of pure geometric form, quickly gained traction among the School’s students. While these abstract artists defended collective work, Chagall defied the system of objectless art promoted by Malevich and his pupils by making mischievous and wry use of its formal vocabulary such as in Cubist Landscape (1919).

“‘The New Art’: Lissitzky and Malevich” focuses on the ramifications of Chagall inviting his friend El Lissitzky to teach in the School’s printing, graphic art, and architecture studios at the start of the 1919 academic year, followed by the arrival of Kazimir Malevich. With Suprematism, Malevich advocated highly distilled abstraction based on simple geometric forms painted in a limited range of colors. This art of pure form moved beyond the physical world, possessing a spiritual dimension. Malevich devised a teaching program that progressively led students from Cubism, Futurism, and Cubo-Futurism, to Suprematism’s detachment from the object. Highlights on view will include rarely-seen paintings by Malevich, who was at this time moving away from painting and focusing on theoretical writings, and several of El Lissitzky’s Proun paintings and drawings. Also included will be Lissitzky’s series of ten lithographs (1923) featuring the figurines he first envisioned in Vitebsk for a staging of the opera Victory Over the Sun (originally performed with live actors in 1913). Never realized, Lissitzky’s idea of replacing actors with figurines or puppets operated by an electromechanical system underscored the opera’s Futuristic character.

“Collective Utopia” will explore the formation of the collective UNOVIS, an acronym for “Affirmers of the New Art,” in February 1920 by the teachers and students of the school at Malevich’s initiative. The members viewed themselves not as individuals but as creative units within UNOVIS. Recognizable by the black square sewn into their jacket sleeves or lapels, its members sought to promote Suprematism and the new in all spheres of social life – a utopian project to transform the world. Full of passion and energy, such artists as Lazar Khidekel, Ilya Chashnik, and Nikolai Suetin designed posters, magazines, banners, ration cards, stage sets, tram cars, and speakers’ rostrums and painted geometric forms of all kinds onto the facades of buildings. A selection of these works will be on view.

The exhibition concludes with “After Vitebsk,” exploring work created by Chagall and Malevich shortly after they left the city. Chagall continued to slyly appropriate and critique the Suprematists’ artwork and aims in his work for the State Jewish Chamber Theater in Moscow, where he lived starting in June 1920. A number of designs he produced for the theater will be on view. The political climate gradually changed after 1921 when the Soviet authorities sought to establish new social and ideological order. In May 1922 the first and last class graduated from the Vitebsk People’s Art School. Soon after, Malevich departed for Petrograd (Saint Petersburg) to continue his research on volumetric Suprematism through the creation of utopian architectural models or Arkhitektons and the design of porcelain objects. A number of these works will be on view.

Chagall, Lissitzky, Malevich: The Russian Avant-Garde in Vitebsk, 1918-1922 is organized by the exhibition curator, Angela Lampe, Curator of Modern Art, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris, in collaboration with Claudia J. Nahson, Morris & Eva Feld Curator, The Jewish Museum, for the New York presentation. The exhibition is being designed by Leslie Gill Architect. The exhibition graphics are being designed by Topos Graphics.

Catalogue

A full-color catalogue, edited by Angela Lampe, the exhibition curator, is being published by Prestel Publishing. The 288-page book will include essays by leading experts on the Russian and Soviet avant-garde, biographies of the artists, and an illustrated chronology of the years 1919 to 1923. The book will be available worldwide and at the Jewish Museum Shop for $60.00.

Public Programs

In conjunction with the exhibition, the Jewish Museum will present a series of public and family programs featuring speakers such as Marc Chagall's granddaughter Bella Meyer on December 6 and noted architect Daniel Libeskind on December 13, and a family day on October 21. Please click here for full schedule.

Support

Chagall, Lissitzky, Malevich: The Russian Avant-Garde in Vitebsk, 1918–1922 is supported through the Samuel Brandt Fund, the David Berg Foundation, the Robert Lehman Foundation, the Centennial Fund, and the Peter Jay Sharp Exhibition Fund. The publication is made possible, in part, by The Malevich Society. The Mobile Tour is supported by Bloomberg Philanthropies.

Press contacts

Anne Scher

212.423.3271 or [email protected]

Daniela Stigh

212.423.3330 or [email protected]

General Press Inquiries:

[email protected]